By Olivia Howard, Third Year Geography

The UK film scene often treats foreign language films as novelties, like high art which can only be watched when feeling especially experimental, cultural and in need of an arthouse to quench such a desire. However, when it comes to awards season every Tom, Dick and Harry claims they have always been a long standing fan of international cinema. Evidently – if this was the case – the films which scoop up said Academy Awards wouldn’t be drying up in the UK’s cinemas.

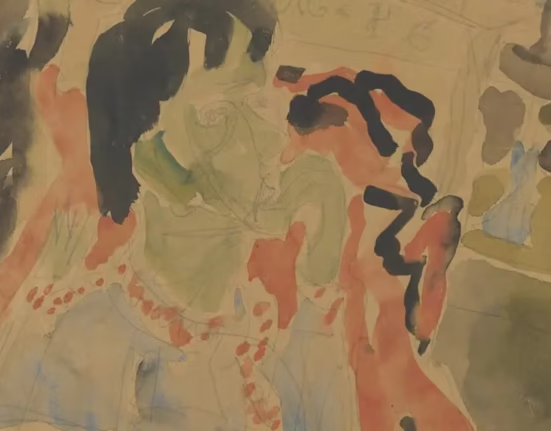

When Parasite (2019), Zone of Interest (2023) and Anatomy Of A Fall (2023) start trending post-Oscars, the UK flocks to watch them. How? On demand. Digital downloads spike, and the directors become household names. Thus, if these films clearly have an audience, why are they so hard to find outside of niche venues like Curzon or Picturehouse?

The answer lies in the self-perpetuating cycle of English-language market domination. European directors like Yorgos Lanthimos, whose most recent film Poor Things (2024) took the Oscars by storm, have all made the switch to English precisely because that’s where the money and recognition lie. They do not need to be commissioned in small arthouse cinemas, considered ‘international films’ when frankly by changing their language they can break out into the mainstream. Jokes, sarcasm and turns of phrase are not lost in translation to the UK and American audiences, and the product is readily consumed.

Multiplex cinemas account for 76% of screens — and barely touch foreign-language films, unless they’re Bollywood movies catering to Britain’s South Asian community. Even Picturehouse, Everyman, and Curzon, once the homes of arthouse cinema, have started screening more mainstream Hollywood fare to stay afloat in the age of on demand streaming services.

The numbers tell a worrying tale. Non-English films saw a staggering 56% decline in box office performance between 2004 and 2014. Take Bollywood out of the equation, and that drop becomes an 82% plummet. The UK Film Council once had a scheme to bribe multiplexes into screening foreign-language films in exchange for digital projectors. But once the Council was dissolved in 2011, so was the initiative.

One common excuse is that British audiences simply don’t have the patience for subtitles. With TV series like Squid Game (2023), Lupin (2021), or Shogun (2024) there’s the option for voice overs or breaks every 45 minutes, not to mention people can mindlessly scroll on their phones. Whereas in the cinema an international film requires two hours of undivided attention, no phone, no talking, complete focus; which in our attention economy is a problem. Further to this, it isn’t just a matter of attention span; it’s a matter of accessibility and exposure. If people only ever see American and British films marketed to them, then of course they’ll gravitate towards them.

With 14 new titles hitting UK cinemas per week, competition is brutal. But that hasn’t stopped Hollywood blockbusters from taking up every available screen. The reality is that British taste is not catered towards foreign films, and film institutions are doing little to change this. If the UK wants to take foreign-language films seriously, a few things need to change.

A List Arthouse festivals, like Cannes or Venice, with real clout and awards alike to the Palme D’Or should be launched into the mainstream UK consciousness. Instead of hoarding foreign films on niche platforms, distributors should push for wider releases in mainstream chains like Odeon and Vue, allowing audiences to view foreign films as a staple, not a niche.

With La Chimera among one of my (and many acclaimed film critics’ may I add!) top 10 films of 2024 without such films on our screens we risk a tragedy of unprecedented proportions. With cinemas acting as vehicles for spreading values within society, a loss of international film will undoubtedly result in a loss of talent, diversity, tolerance and curiosity in our cinemas. It reinforces the use of English globally, promotes the oversimplification of cultures, heritages, languages, traditions, and slowly ciphers British people off to consider limited perspectives on the manly complex themes films encapsulate.

How do you think the UK’s cinema scene is shifting and do you think it is changing how foreign language films are considered?

Featured Image courtesy of IMDb – Anatomy of a Fall (2023)