Away from the cameras and busy press conference rooms, and the immediacy of a game just played, there is an opportunity for a manager to reflect a little more.

Speaking with Fabian Hurzeler at Brighton & Hove Albion’s training ground alongside a small group of reporters, following a brilliant start to life on the south coast, it was a fascinating chance to delve into how someone goes about becoming the youngest manager in Premier League history.

Much, of course, has been made of Hurzeler’s age. At 31, he is the youngest permanent manager in Premier League history. Ryan Mason, at 29, was younger, but only an interim. The next youngest full-time were Chris Coleman, at 32, and Gianluca Vialli, 33.

Yet not as much is known about all the components that have shaped such a young high achiever. His fiercely competitive and hard-working family, his inner salesman, his fascination with mindset and reading about the modern tech titans.

Spending an hour in Hurzeler’s company, it is clear his own impressive achievement is in no small part down to his strong desire to keep learning and enviable communication skills, taking time to weigh every word, frequently making gestures with his fingers, as though he can almost touch the ideas he expresses.

On a day-to-day level, he explains, he is too busy to go out during the week, although might allow himself a night out with friends at the weekend after a win.

He watches no TV shows or films, and isn’t interested in football pundit shows – “If I was to listen to every expert talking about our club, I think I would destroy myself.”

He listens to podcasts and reads, but, again, it is all with self-improvement in mind, rather than escapism. The books are about mindsets, or famous figures.

“How is the mindset from high performance people, like Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg,” he says. “For me I like to understand it, how they behave, how they get so successful.”

It’s become a cliche for football managers, but he also watches loads of football. Analysing strategies, borrowing ideas, taking mental notes. Even his idea of relaxing is chatting with friends while a game is on.

He does like padel, the tennis/squash hybrid that has become popular in recent years – “I’m pushing hard that we get some padel courts here in the training ground” – but beyond that it is all football, football, football.

“That’s my inner conviction,” he says. “It’s the same in any other job. You see repetition, game to game, pattern to pattern. The more things you see you also focus more on details, the more things you learn on details.”

Hurzeler is big on sharing. For the Uefa Pro Licence in Germany participants must organise a week of work experience at a football club and he went to Nordsjaelland, in Denmark. Coaches there are expected to travel to Brighton to reciprocate.

Hurzeler will speak with trusted other coaches in Germany about ideas, how to tackle certain opponents and outwit particular managers.

Supplementing that inquisitive mind is a fiercely competitive upbringing that has never left him. When the Hurzeler family get together, Fabian and his three siblings compete at Uno, the addictive card game, or Catan, a German strategy game, with the same determination he conjures trying to beat Manchester City.

“When I’m sitting with my family, let’s say at Christmas time and we played games and I lost the game, the night was over for me,” he says.

“We are all made of the same blood. That’s how I grew up, it was a competition all the time, and that’s why I’m very competitive.

“It’s still like when we were young, playing games, coming together, talking, being competitive, no matter what we are doing. This will never change. I am very happy that my mother tries more to control these things, keep the dynamic positive.”

All four have achieved highly in their fields: his brother is a pilot, one sister is a business consultant, the other a strength coach at an American Football team.

Their parents set the tone with diligence and hard work.

Hurzeler vividly remembers every morning his father would be ready at 6.30am with their bikes. He would cycle to the train station to catch a train to school, his father on to work at his dentist practice. On rainy days Hurzeler would beg for a lift in the car, but they always cycled.

At that stage, Hurzeler was at Bayern Munich’s academy and on course to be a Bundesliga player. Though he was a clever player and captain throughout, he found he wasn’t the best at anything: not the fastest, couldn’t defend in his box, or really score at the other end.

When it came to pushing for a place in the seniors, none of it was quite enough to stay at the top. He wanted to be part of the elite but knew, inside, that prospect, as a player at least, was dwindling.

After his first pre-season following a move to Hoffenheim the manager told him he wasn’t in his plans and he was back playing with the Under-23s. “I started being a coach from that point,” he recalls. He was 21 years old.

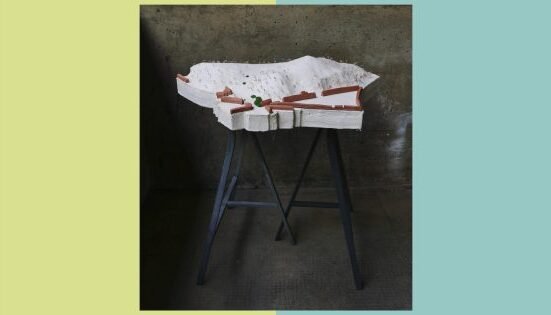

It was a significant shift. He had to take other jobs to pay rent and bills. At Pipinsried, where he first became player-manager, he spent time working as an art dealer. He was fired when his manager realised he spent more time watching football than making sales, but it taught him a lot.

“There was an interesting thing about selling these paintings, because if you want to sell something to a person, you have to try to convince him by doing something,” he says.

“And you can’t go there and say, Look at this picture. It’s an amazing picture. It’s an amazing painting and it’s from Roy Lichtenstein or Damien Hirst. What an amazing artist he was, blah, blah, blah.

“No, it was more like, if you really want to sell something, and that’s a little bit similar to being a coach, you have to understand the needs and the wishes from the clients. So you can’t go there and say, Look at the picture. It’s completely different.

“You have to go there and ask: What are you looking for? What are your needs? What are your interests in life? What are your wishes?

“And it’s a little bit similar to the players. So the most important thing is to understand the person behind the player. So what are his needs? What are his values? How is he educated? How was his past?

“How is the culture, for example, in Gambia with Yankuba Minteh or Simon Adingra in Cote d’Ivoire? In comparison, for example, with James Milner, it’s completely different.”

Hurzeler will listen to his players after games, to discover if his ideas are getting through, if they are easy enough to understand, what players dislike about an approach, how it can be tweaked to make it translate better through them onto the pitch.

He makes the final decisions, but he is fully aware that players need to be convinced by what he is telling them.

“The most important is to reflect on it, analyse it together, also listen to the players and then make a clear decision where everyone is on the same page and then you completely do it. But I think in general, the style of play is we will always try to play out from the back, because in the end it’s the identity. But it’s finding a balance.”

Hurzeler surrounds himself with people unafraid of criticising him.

“You get enough compliments when you do great things. But for me, it’s more important to get critical feedback because compliments won’t help you in your development.”

He was taught to adapt by harsh lessons in the lower rungs of German football. He recalls the first time discovering football’s brutal nature after he won promotion with Pipinsried to the fourth tier of German football then lost the first seven games. His phone rang while he was sitting in a coffee shop and it was a journalist asking, “Do you think if you lose the next game, then you’ll still be the coach or not?”

It was a jolt. This was, after all, only the fourth tier, and he was only in his early 20s. But this is how much it mattered.

Hurzeler didn’t panic, but he did adapt. They had won promotion playing possession football and his stubbornness and determination to control the opposition had blinded him to what wasn’t working.

He found that winning was about balance, adaptation, flexibility, more than finding a set style and sticking rigorously to it, even in the face of failure.

“You won’t learn being a coach by doing only the licences or by reading a book and trying to go after the book,” he says. “It’s more about making your own mistakes, having your own experiences and then learning from this experience.”

And later he came to the realisation that for all the wonderment in “pure”, aesthetic football, usually defences win titles and trophies.

At St Pauli “we won the championship because of our defence”, he says of the promotion to the Bundesliga last season that convinced Brighton to appoint him. Then reels off the statistic that on average in the last eight seasons the Premier League winners have conceded fewer than 31 goals.

“Defence wins championships. It’s an old sentence but, in the end, it’s the truth.”

In the pursuit of magnificent football, sometimes it gets lost that a 1-0 scraped victory can be entertaining in its own way. It is something that has been ingrained in Hurzeler since the beginning.

“It was always about winning the game. That’s something that was deep in the DNA at Bayern Munich.

“You have to go to every game to win it, to every tournament, no matter if you were 12, 14 or 16 years old, you have to go there and win the game.”

And there is one more component that Hurzeler places great importance on.

“It’s also an important thing to have humour in this building, like fun, enjoying it, not to be always on point because in the end they should also have fun at work,” he says.

“Because I learned one sentence from Tony Bloom: if you enjoy what you are doing, the luck will come.”

Which is ironic, because it sounds as though there is nothing lucky about what Hurzeler has achieved.