For years, I’ve been fascinated by how museums and exhibitions can create powerful, thought-provoking experiences. I enjoy going to spaces such as the Wellcome Collection and the Science Gallery where art, science, and storytelling merge, making complex topics like health and illness accessible and relatable to the public.

This inspiration fueled my interest in founding Soul Relics Museum, a community project that focuses on using objects to tell stories about emotions and wellbeing. Past projects have focused on mental health awareness (e.g. at Poplar Union, a community centre in East London), stories of migration and forced migration among the Chinese and Vietnamese communities in London, and stories of healthcare professionals during the Covid-19 lockdown.

More recently, I am leading on an exhibition on eating disorder recovery at Somerset House (East Wing) in London as part of the Festival of Social Science. The exhibition is part of EDIFY (EDIFY = Eating Disorders: Delineating illness and recovery trajectories to inform personalised prevention and early intervention in young people). EDIFY is a four-year programme of research led by Professor Ulrike Schmidt, King’s College London and Dr Helen Sharpe, University of Edinburgh. The workstreams span projects in the arts and humanities right through to state-of-the-art scientific research in informatics and neuroscience. This interdisciplinary approach allows us to build a rich picture of the different reasons why young people develop eating disorders, how these illnesses progress, and what we can do to promote lasting recovery.

Challenging Perspectives – The exhibition

The exhibition centres on the often-overlooked experiences of recovery from eating disorders (ED) among diverse and underrepresented populations.

A key aspect of the exhibition is the inclusion of personal objects and photography that capture pivotal ‘turning points’ in recovery. One section, Research on Turning Points in Recovery, displays findings from a qualitative study that explores these transformative moments. Personal objects, chosen by participants from diverse and underserved backgrounds, serve as symbolic representations of their recovery journeys. These objects, carrying deep emotional significance, also challenge the stereotypical imagery of eating disorders commonly seen in the media.

In another two-part display, ‘Inside Out’ and ‘Inversions‘, young people with lived experience of ED took part in a participatory photography workshop which provides a visual dialogue between illness and recovery, inviting the audience to engage with the personal reflections of participants. In both of these sections, Photovoice, a participatory research method, plays a central role here – participants share their experiences through photographs and then co-construct narratives during group workshops.

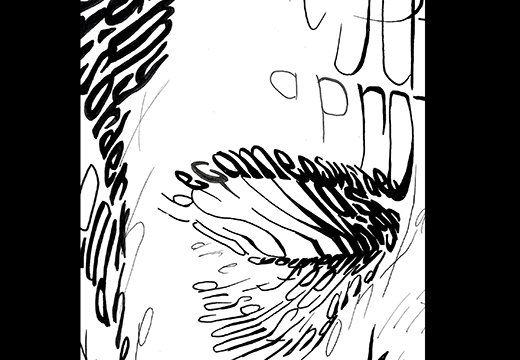

Another section, Lines Telling Stories: Men and Eating Disorders, uses collaborative word-portraits to highlight men’s lived experiences with eating disorders, another often-overlooked topic in ED discourse. Partnering with artists and academics, this section confronts the stereotype that ED predominantly affects women, providing new perspectives on how men engage with the complexities of illness and recovery.

Why Psychologists should care about public engagement

Public engagement is an essential bridge between academia and the broader world. Underserved communities –those from racially minoritised backgrounds, lower socioeconomic status, and those with diverse sexual, gender, and neurodiverse identities – ofen face significant barriers to treatment and are less likely to be represented in research. By integrating visual methods like photography and object-based storytelling, the exhibition offers an inclusive platform to share these voices.

Public engagement through the arts can inspire change not just on an individual level but within entire communities and institutions. By creating immersive experiences, we can spark conversations and shift public attitudes toward mental health issues, fostering a greater understanding of mental health including eating disorders.

What we learned from the exhibition process

One of the most significant aspects of this exhibition was its participatory nature. Through the participatory workshops, I have reflected what I learnt from the participants.

Letting Stories Speak for Themselves: Rather than explicitly naming intersecting identities, we allowed the narratives to unfold organically, highlighting how eating disorders can impact people from all walks of life. This was important because many recovery stories are often simplified to focus on identities that fit into preconceived categories, potentially alienating others whose experiences don’t align.

Focus on Recovery, Not Illness: Some participants mentioned that much of the existing eating disorder research focuses on people who are currently ill, and they were glad to see that this research project and exhibition focused on recovery. It emphasises the importance of research that not only looks at the illness but also explores what recovery looks like – and how it’s experienced – across diverse populations.

Challenging Stereotypes in Media Representations: The imagery around eating disorders is often limited to thin figures or food-related images, which can reinforce harmful stereotypes. Surprisingly, none of the objects and photos chosen by participants featured the typical images found on Google search of eating disorders, where participants hope that the exhibition will help move beyond the oversimplified images that dominate media portrayals.

A call to Psychologists

Public engagement is about telling stories, breaking down barriers, and inspiring people to think, feel, and act differently. As psychologists, we have the unique ability to make a real difference in people’s lives. Although this may sound ambitious, public engagement is not just about communicating research, it is also about moving towards a greater understanding, empathy, and healing.

The exhibition is open from Mon-Fri (9:30-4:30) at Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing between October 14-October 25, with an evening opening from 5:30-8 pm on Oct 17.

Image above: ‘Lines Telling, part of a word portrait from the spoken words by the men in collaboration with artist Gary Dadd with Professor Heike Bartel at the University of Nottingham.