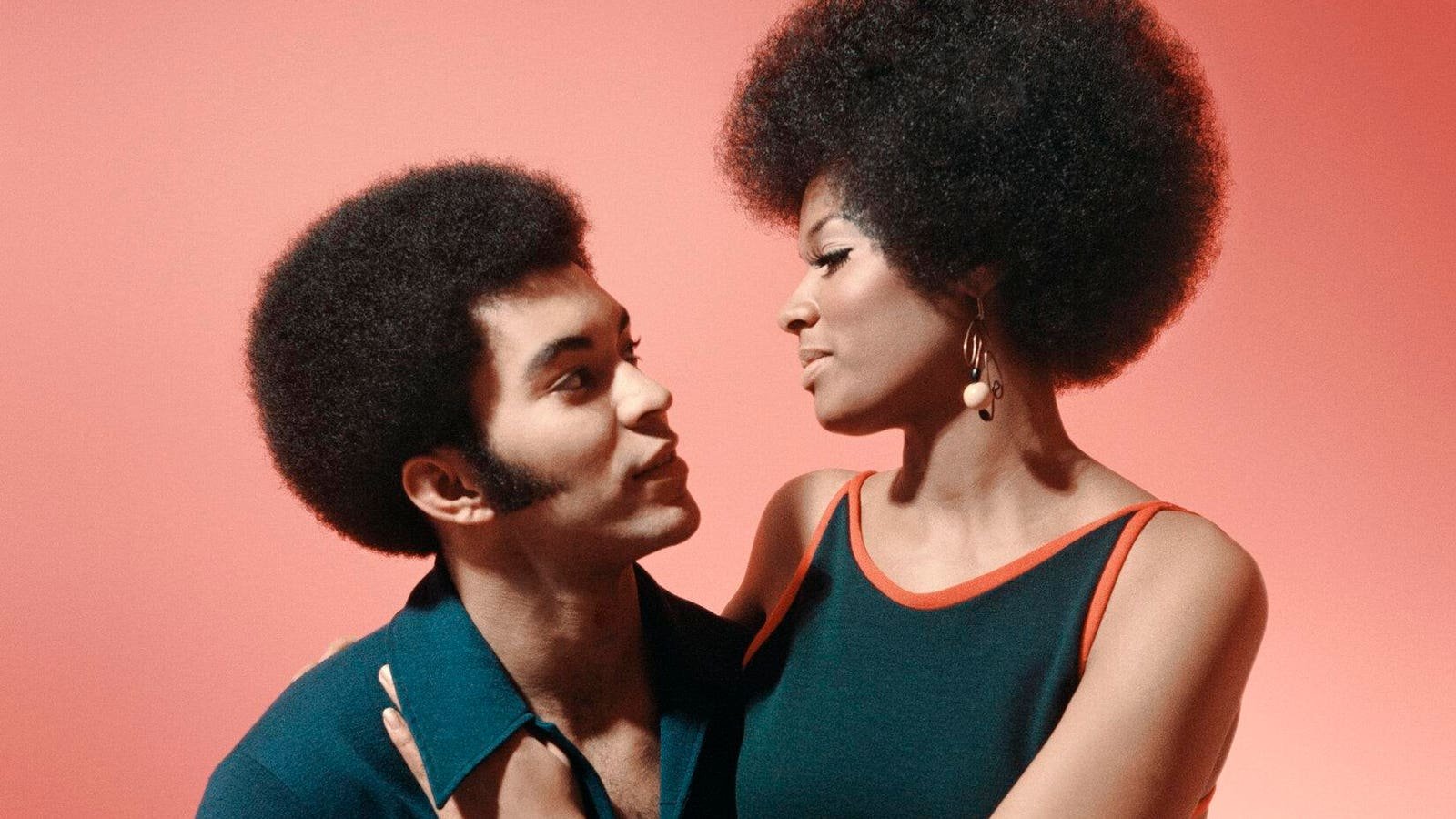

Kwame Brathwaite, ‘Untitled (Couple’s Embrace),’ 1971 c. Archival pigment print, mounted and framed. Courtesy of Philip Martin Gallery and The Kwame Brathwaite Archive.

© Estate of Kwame Brathwaite

“Kwame Brathwaite: The 1970s” at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts in Little Rock contradicts what museumgoers expect from photography exhibitions.

For starters, the photos are in color, not black and white. Technicolor. That super 1970s saturated color. “Soul Train” color. Rich. Vivid.

Secondly, the subjects are contemporary. Contemporary to the 70s anyway. Forget stilted pictures of Gilded Age society debutants or industrialists, Brathwaite’s models are hip. Fly. They look ready to walk right out of the picture frame and get down, get on stage, walk a runway.

Most unconventionally, the photographs depict African Americans. Aspirational African Americans. Idealized African Americans. Smiling African Americans. African Americans posed in high fashion, successful, happy, not being beaten on by police, protesting being beaten on by police, or living in poverty–the way Black people are routinely depicted in museum exhibitions.

That shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows Brathwaite (1938–2023). His photographs helped create the visual overture for the Black is Beautiful Movement of the late 50s and early 60s.

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, “The phrase ‘black is beautiful’ referred to a broad embrace of black culture and identity. It called for an appreciation of the black past as a worthy legacy, and it inspired cultural pride in contemporary black achievements.”

Brathwaite’s pictures, organizing, and promotion helped create momentum for the slogan. The Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts new presentation highlights 16 of the artist’s independent studio works created subsequently, during the 1970s.

“This exhibition takes a look at Brathwaite’s evolution as an artist in the 1970s—an era where his camera moved from documenting a movement to exploring deeply personal and creative narratives,” Catherine Walworth, the Jackye and Curtis Finch, Jr., Curator of Drawings at AMFA, said.

“Kwame Brathwaite: The 1970s” shows a more experimental and expressive side of Brathwaite’s photography—one where color, composition, and cultural storytelling take center stage.

Kwame Brathwaite Photography In The 1970s

Kwame Brathwaite, ‘Untitled, Models in parking lot. New York, NY,’ 1972, c. Archival pigment print, mounted and framed.

Courtesy of Philip Martin Gallery and The Kwame Brathwaite Archive.

By the 70’s, Brathwaite’s star had risen to the point of being one of the top concert photographers, shaping the images of such figures as Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, and James Brown.

Building on his activist roots from the African Jazz Art Society and Studios and Grandassa Models, this period highlights Brathwaite’s mastery of light and form, and his continued commitment to celebrating Black identity and creativity.

For background, Brathwaite co-founded the African Jazz Arts Society and Studios in 1956 as a teen along with his older brother. The collective brought together creatives across multiple disciplines. They also founded the Grandassa Models in 1962, a modeling troupe for Black women challenging white beauty standards. “Grandassa” is taken from the term “Grandassaland,” the name Black nationalist Carlos Cooks used to refer to Africa.

“There was an intentionality to this interdisciplinary group of very young people coming out of design school in the mid-1950s,” Walworth told Forbes.com. “Brathwaite, his brother Elombe (Brath), and the other members of the African Jazz Art Society and Studio, used their creative skills to actively support the Black community. They were also members of Carlos Cook’s African Nationalist Pioneer Movement and took much of their philosophy and activist direction from that movement. The overarching aim was to uplift Black people, and all of Brathwaite’s work can be seen through that lens of advancement, promotion, pride, and love.”

Like all great artists, his creativity evolved. “Kwame Brathwaite: The 1970s,” focuses on that evolution.

“This exhibition builds on his 1950s and 1960s collective action, but pivots to focus on Brathwaite’s independent commercial studio practice in the 1970s,” Walworth explained. “Images on view show him capturing a new generation of performers like Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder on larger stages.”

All in bold color.

Walworth specifically selected only color photographs for the show.

“Brathwaite started out as a black and white photographer, and those images are magical. They really meet the subject matter where it is at—especially jazz clubs throughout New York and its boroughs in the late 1950s and 1960s. We also tend to think of those historical eras as black-and-white worlds, before color photography entered the picture in a big way, but I particularly love his color images. I find them unforgettable, and each portrait has its own defining palette—one that shifts a bit in the 1970s to brighter tones,” Walworth said. “To me, he has a painter’s sense of color and it makes the exhibition feel exuberant. I also think that he used color strategically to evoke an emotional glow around his subjects.”

A positive glow. Celebratory.

“Both as part of the AJASS collective and in his studio practice, he uplifted musicians, models, and individuals like jewelry designer Carolee Prince, who is featured in the exhibition wearing a pair of her own earrings,” Walworth said. “With the images in this exhibition from the 1970s, we see him not only supporting professional creatives, but generally putting light and joy into the world.”

Light and joy with a Black face.

African American trauma has been well documented in photography and art–and needs to be, continues to be–it has often been presented, however, to the exclusion of Black joy, and celebration, and achievement, and love. Brathwaite worked to correct that imbalance throughout his career.

‘New’ Kwame Brathwaite Photographs

Installation view of “Kwame Brathwaite: The 1970s,” at Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts.

Jason Masters; Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts

Working with The Kwame Brathwaite Archive, the exhibition features three never-before-seen images. The newly released pictures include portraits of model and designer Carolee Prince, singer and songwriter Teddy Pendergrass, and a striking group shot of four models against a purple background.

“In the case of the four models with a purple background, I was able to choose from two different options from the same shoot and think about the impact of subtle differences,” Walworth explained. “(The Kwame Brathwaite Archive) is a physical archive with original negatives, contact sheets, slides, prints, and the artist’s own notes and writings. Every now and then when the moment is right, Robynn (Brathwaite) and Kwame Brathwaite, Jr. follow the artist’s expressed wishes and release something new.”

On July 31, 2025, Brathwaite, Jr., the artist’s son, will share his unique and personal perspective on Brathwaite’s work and legacy during a talk at the AMFA. Guests will learn about Kwame Brathwaite’s powerful photography and its lasting impact on Black identity and culture. Tickets are free, but registration is recommended at events.arkmfa.org.

“Kwame Brathwaite: The 1970s,” can be seen through October 12, 2025.