Digital art and its logical conclusion, AI-generated art, has become a significant topic of discussion lately. With the proliferation of deepfakes on social media and the twee designs of apps that gamify daily life, digital art is an inescapable part of modern life. While computers have made some aspects of image-making easier, like touch-ups and compositing, the tools only reflect the intentions of their users. Still, despite the multiple factors that have given “digital” a bad name, some use computer-based tools to toil, tinker and produce works that could truly be said to have artistic merit. One such artist is Jordan Speer, whose works recall Peter Saul stripped of political messaging and rendered through a Dungeons & Dragons handbook.

Speer’s prolific output can be found in the pages of various print sources, like Bloomberg Businessweek, and posters for bands like the Aussie garage rockers King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard. There’s no doubt that there are commercial necessities tied to the full-time practice of any artist attempting to sustain themselves through practice alone, but Speer’s art — including images produced for pay-to-read articles — is different. Through the artist’s website (and its necessary social media apparatuses), fans can find an array of compositions that are the work of a distinct voice, ranging in theme from cyberpunk and meatgrinder battlegrounds to dungeon-crawling excursions.

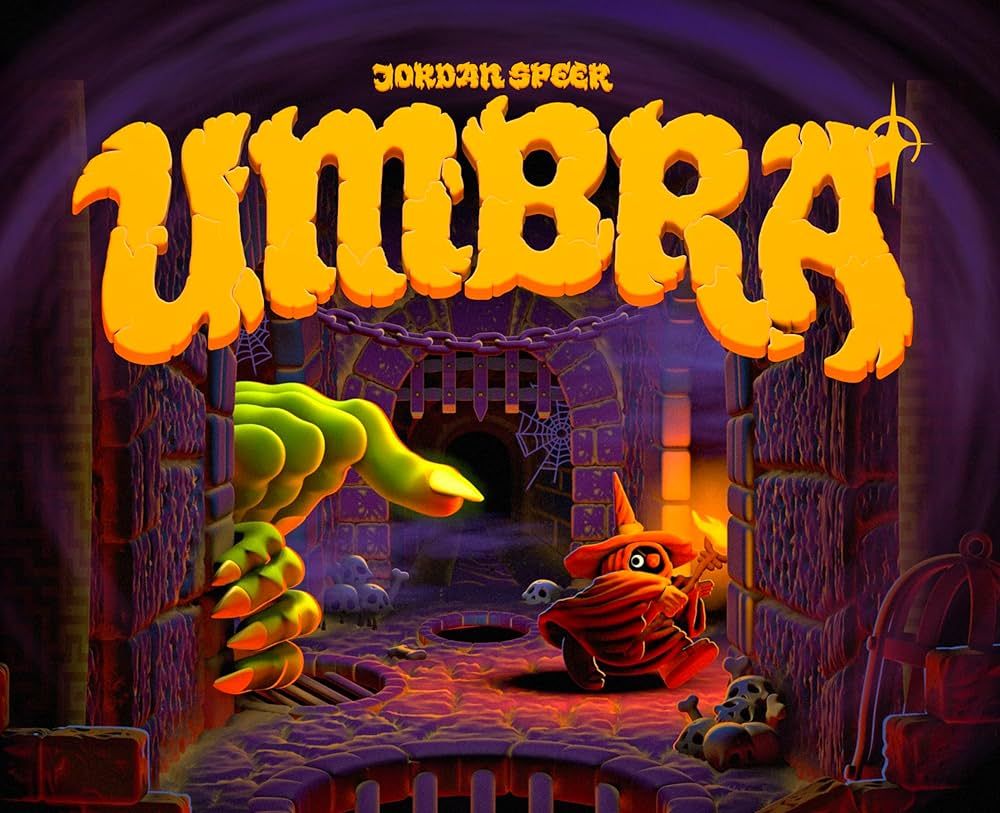

With emphasis on this latter style, Speer created his first book, Umbra, out on October 29 from the ever-reliable source of inspiration, McSweeney’s. Umbra isn’t the work of someone who makes user-friendly art to accompany subscription renewal emails, but an artist who’s unabashedly interested in reinterpreting a collective memory of once-in-a-lifetime flea market finds.

Umbra Offers a Concentrated Dose of Jordan Speer’s Stellar Art

The Book Is a Familiar but Distinct Take on Fantasy

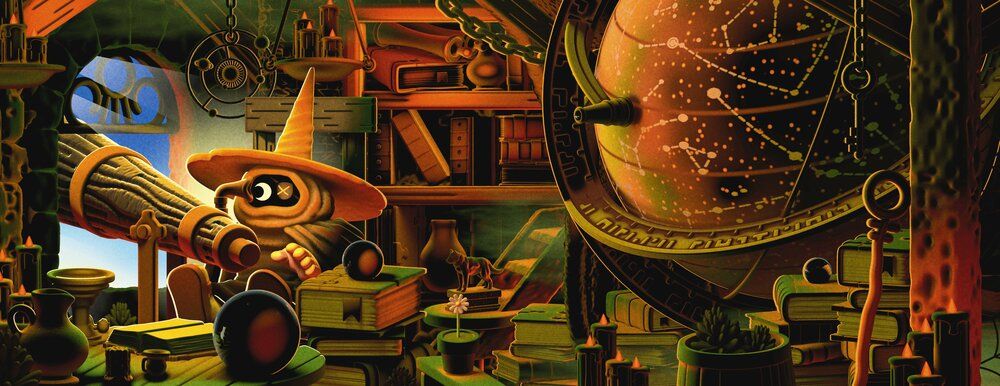

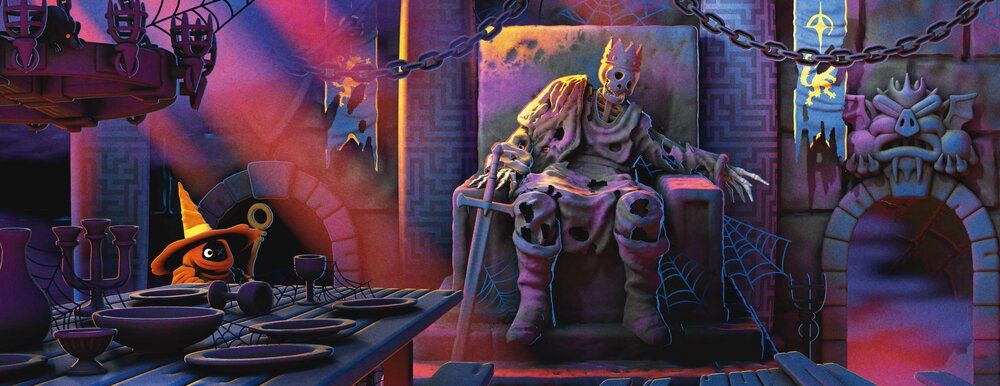

Umbra is a picture book intended for a young audience. It’s sequential, wordless, and visually suggestive for easy comprehension. In many ways, the book is an expected step for someone whose standalone pieces already suggest involving nerdy lore. In this single-volume context, Speer’s step toward more explicit storytelling sits between his best one-off pieces and the video works he’s created for design studios like Brain Dead. Those who haven’t checked out Gremlin Foundry should do so right now. What’s most striking about Umbra’s art are the pops of neon, impressive compositional considerations, and a sense of tactile reality. Despite Speer being a digital artist, there are dings and tasteful blemishes in his works to suggest a physical hand at work. A hand that is tastefully imprecise and lovingly crafted.

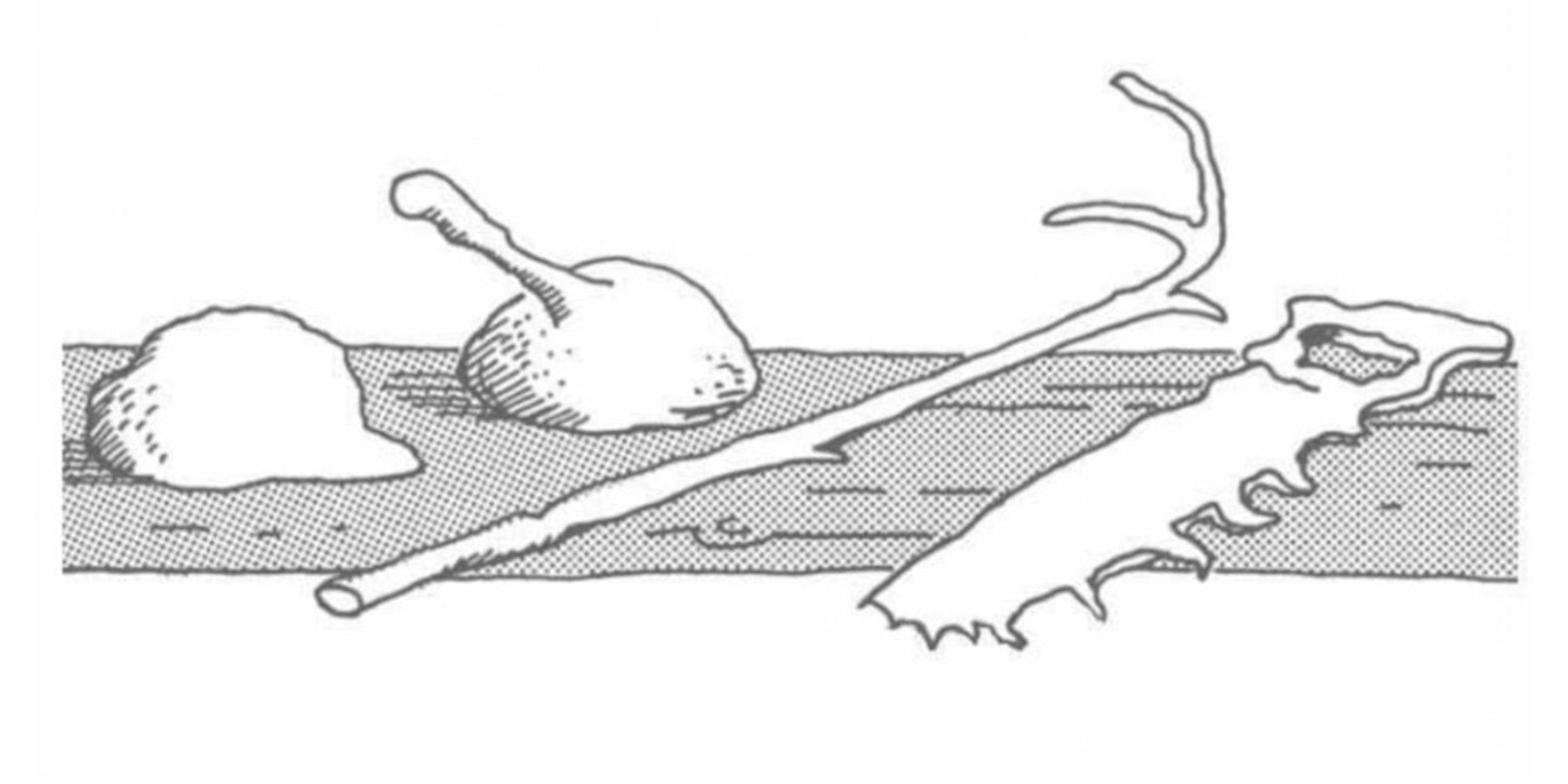

Without accompanying text, Umbra is an easily digestible narrative that makes no changes to its basic and time-tested premise. Here, a brave wizard sets forth on an epic adventure to undo the wrongs of a monocular, ironclad villain. Through forests, wastelands, and other fantastical locales, the wizard faces the threat of expanding darkness and industrialization wreaking havoc across the natural world. Princess Mononoke and FernGully: The Last Rainforest immediately come to mind, both of which were also composed with the meaningful, measured implementation of digital tools. It wouldn’t be surprising if Speer looked to these movies for inspiration when working on Umbra.

1:35

Related

The Far Side’s Most Confusing Comic, Explained

In the latest Comic Book Legends Revealed, discover the time The Far Side’s Gary Larson had to explain a joke to every paper that carried the strip.

The wizard’s journey in Umbra leads to encounters with ogres, goblins, giants, and monsters of all kinds. Though they may be familiar fantasy characters, Speer renders them in a near-plasticine style that’s enhanced with unnatural hues. Umbra‘s story is for kids, but its art tickles the fancy of those who enjoy thumbing through a stack of something as stylistically dirty and grimy as Garbage Pail Kids. Following every visible stink line to see the suggestion of motion on each page gives Umbra a sense of life, and imbues its decrepit yet gorgeous lived-in world its soul.

Umbra Is for Kids, but Adults Might Get More Out of Its Art & Pages

The Book Recalls Nostalgic ‘80s and ‘90s Pop Culture

A profound sense of nostalgia is tied to Speer’s art, like a half-forgotten memory sitting on the tip of the reader’s tongue. It’s impossible to look at any of his digital creations and not think, “What is that from?” Speer’s bright and meaty pieces recall the era of gray video game cartridges, when the box art bore little resemblance to the actual game. There are also hints of Kenner’s late-80s toy line for The Real Ghostbusters, which produced funky art for clunky toys like “Fearsome Flush,” an anthropomorphically off-putting toilet. This influence can be seen in the soft airbrush-like shading and atomic glow of Speer’s colors. Despite myriad stylistic forebears that smack distinctly of the ’80s and ’90s, Speer’s work is original but comes at the reader like a transmission from an adjacent reality — familiar, comforting, but still hazy.

Ostensibly, Umbra is for kids, which means that young readers will approach the material without preconceived notions. That is, of course, unless they’re growing up in one of those pop-savvy Millennial museum households. There’s something special about this: a kid can sit and scan the pages, free of words, free of context, and receive its intended transmission. In the best of all outcomes, they will then be inspired to produce their own art, building a new lineage from Umbra‘s influence.

Related

The Notorious Animated Zelda Series is Way Better Than We Remember, Memes and All

The 1989 cartoon brought the adventures of Link and Princess Zelda to life in ways their video games never could!

For adults, the cross-pollination of high- and lowbrow Millennial interests is readily apparent and unoriginal in conceit, even though its execution is distinctly Speer’s own. That said, Umbra is not a book meant to radically change the landscape defined by didactic texts about tying shoes or being kind to others. Here’s an homage to the art that has slipped through the cracks without any prescribed meaning other than what people impose on it. Compared to, say, seminal classics like Jon Sciezka’s The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, Tomie dePaola’s Strega Nona, or even the striking, authentic object photographs made by Walter Wick for I Spy, Umbra is a handsome book that has the potential to worm its way into young minds and take up residence as a reference point just like the others.

Umbra Uses Modern Means to Hearken Back to a Bygone Era of Art

The Book Is the Best and Most Artistic Kind of Nostalgic Throwback

Umbra, like its shelf-mates, is a lot of fun to look at. The sheer radiance of the imagery, across Zelda-like landscapes of dingy dungeons and detritus-filled deserts, more than makes up for its lack of words with meticulous attention to detail. Would Umbra thrive if it took a cue or two from Where’s Waldo? (or Where’s Wally? outside North America), providing spot-the-recurring-character details? Probably, but people will gravitate to aspects at their own discretion, and that’s more than enough.

For adults who take more than a healthy amount of time to consider the implications of commercialism and digitization, Umbra makes a case for the lone artist forging a path antithetical to the endless array of “content” that sears people’s eyeballs and numbs them to good art. Through Umbra, Speer invokes a bygone era through modern means. There was once a time when the ads in comic books weren’t solely about buying the next thing, but building lore within the pages of other stories. Flipping through the pages of any pre-2000 comic book and scanning the ads within proves as much.

Related

Final Cut Review: Charles Burns Returns With a Complex Meta-Commentary About Being a Comic Artist

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel is an artist at the peak of his powers looking back on some of his favorite subjects from a new vantage.

Art departments once considered composition beyond 2D legibility and the aestheticization of everyday life. Art was big, bold, cluttered, and guided by artists’ interests in contrast to commercial standards. Even in the most egregious examples of art being used to sell tie-in statuettes for too much money and too few points of articulation, there were still enough visual cues to inspire individuals to take up the pen. The same can’t be said for most of today’s mainstream art, which is so often driven by naked monetary gain above all else. The fact that this intent is rarely (if ever) hidden only makes the current creative space feel more dire. Exceptions do exist, but they’re too few and far between.

Umbra, in contrast, does the opposite. The book is Speer’s genuine artistic expression, and he clearly made it for more than just turning a profit. Umbra may be commercial art, but it’s anything but soulless and cynical. As proven by Umbra, Speer — like the artists who inspired his work — is at his best when his art allows readers to fill in the blanks and go out into the world, wholly invigorated by the possibility of creation and discovery.

Umbra will be sold wherever books are available on October 29, 2024 from McSweeney’s.