The centenary of Sorolla opened at a Royal Palace, that of Milan, and now concludes at the one in Madrid, in the Gallery of the Royal Collections, which from today until February 16 will host the 77 paintings of Sorolla, one hundred years of modernity, canvases that have arrived from New York, Paris, many private collections, and from the Sorolla Museum in Madrid itself, closed for renovations until 2026. Although the star is undoubtedly a painting that has been missing for over a century and whose existence was uncertain: Boulevard in Paris, last seen in 1890, reflecting a completely unusual theme for Sorolla, everyday life in the Parisian cafes of the time, a subject often depicted by French Impressionists. A painting that reappeared when its owners decided to clean it and have it appraised. Additionally, the beautiful Giralda, Sevilla (1908) had not been exhibited since the painter’s death.

‘Boulevard in París’ (1890), by Sorolla

“This is an exhibition to showcase how well Sorolla paints and to display him in his most complete aspect,” emphasizes Consuelo Luca de Tena, curator of the exhibition along with Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the painter’s great-granddaughter, and Enrique Varela, the current director of the Sorolla Museum. Varela has highlighted that in the more than 40 exhibitions of the Sorolla Year, there have often been “small and specific looks at his figure and his work, from his early training stage in Valencia at the age of four in Rome or his relationship with the Valencian school. We were clear that the last exhibition should lose that particular, specific look to make a global approach, a final swan song, a golden brooch with which to make a global vision around his figure.”

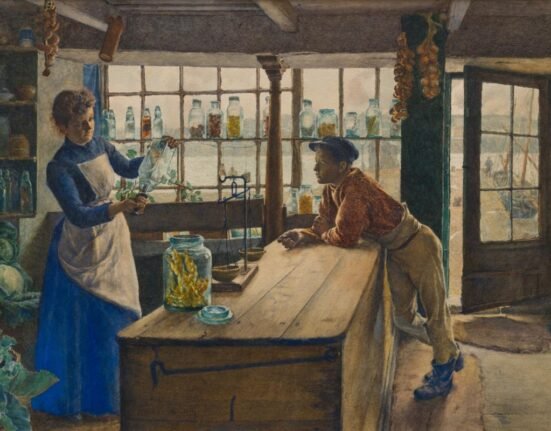

‘The Peppers’ (1903)

A brooch that begins with its social painting, portraying the harsh life of fishermen, female workers packing raisins, procurers in a train car with young girls who will be prostituted, and concludes with magnificent landscapes, many from her own garden at her home in Madrid, where she suffered a stroke in 1920 at the age of 57 while painting Mabel Rick under the pergola. The years of hard work had taken a toll on her health, and she would never paint again. She would pass away in Cercedilla at her daughter María’s home on August 10, 1923, and would be buried in Valencia with the honors of a general captain.

‘After the Bath’ (1902), by Joaquín Sorolla

“We have sought to bring together works from his entire career, from his youth to maturity, encompassing all the themes he explored throughout his life. The exhibition is divided into five sections. The first one is the path to success. This title is not chosen lightly, as Sorolla, in his early years as a painter, was determined to become an international artist, one who could rival the most prominent figures. He was aware that, at that time, the most effective way to gain recognition was to participate in major competitions, particularly the salons of Paris.”

‘The Return from Fishing’ by the Musée d’Orsay

“If you take a look at the catalogs of these salons,” he continues, “it is amazing, among the multitude of artists, who could be two thousand or three thousand, the few that have remained. And among those few is Sorolla, who carved out his path through that kind of jungle and conquered his place among the international painting scene. Very soon, the French State bought a beautiful painting that we have on display, which is The Return from Fishing, and from there his career continued.” A career, he says, in which even when he creates social painting, he is more interested in the formal problems of color and light.

‘Stroll along the seaside’, by Sorolla

The section dedicated to the sea is the largest in the exhibition. They are the paintings that gave him greater popularity and it is where Sorolla expresses his temperament to the fullest, where he can give free rein to his immense desire to capture light in the most interesting moments of the day. In his time, all painters were interested in light, but in his case, it is so concrete, so precise, that it gives us the sensation that Sorolla has stalked it to seize the precise moment when it was at its best. He gives the paintings a reality and a vitality that gives the feeling that it is truly a snapshot that has captured an unrepeatable moment. This was very well expressed by Pérez de Ayala when he met him and said that he was as if possessed by an impatience, by a tragic urgency, in that pursuit of the unrepeatable moment that characterized his entire life and production,” notes the curator.

“The Family” (1901), by Sorolla

A sample in which his children and his beautiful wife Clotilde, whom he used as models and experimented with, are continuously present, evolving with time until reaching one of the paintings that closes the exhibition, Clotilde in the Garden, from 1919 or 1920, with an older Clotilde, dressed in cream, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, with a gaze as serene as ever but revealing the passage of years.