Upon entering Room 15 of London’s National Gallery, visitors are mesmerized by the painting in the background. Samson — a giant, bare-chested mass of muscle — rests, exhausted, on Delilah’s lap. Her bare breasts are revealed. An accomplice of the beautiful Philistine cuts the Israelite colossus’s hair with scissors, robbing him of his strength.

Samson and Delilah — painted between 1609 and 1610 — is one of the 30 masterpieces in the National Gallery’s permanent collection that are attributed to the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens. The controversy over the work’s authorship — a debate that has been going on for almost 40 years — is one of the most intense and aggressive in the art world.

“It was the first time I saw it: it was 1987, at the National Gallery. In the blink of an eye, I immediately realized it wasn’t a Rubens. It was a cheap copy of the kind you see displayed on Sundays along Bayswater Road, [where painters hang their works on the fence surrounding London’s Hyde Park],” explains painter and art historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis, in a phone call with EL PAÍS from Athens.

Doxiadis has dedicated half of her life to disproving the painting’s authorship. She leads an international group of art critics. Her decades of research have been published in a book titled NG6461: The Fake Rubens (a reference to the work’s catalog number at the National Gallery). Released this past March, it has revived the battle between the art historian and the London museum.

To fully understand this story, it’s important to reconstruct the facts, closely observe the painting’s brushstrokes, travel back in time and — above all — apply a necessary dose of skepticism to the certainties and the theories defended by both sides of the debate.

Rubens painted Samson and Delilah at the beginning of his mature period, in the early-17th century. He had just returned from a long trip to Italy, where he learned from Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo and Leonardo. But, above all, he was seduced by a transgressive, revolutionary artist, known for his powerful use of light and strokes, named Caravaggio.

It’s quite possible that the work was commissioned by his friend and mentor, Nicolaas Rockox (1560-1640). Then-mayor of Antwerp, Rockox’s house is now a museum. No one doubts that the painting existed, but when Rockox died in 1640, it disappeared — like many other famous paintings.

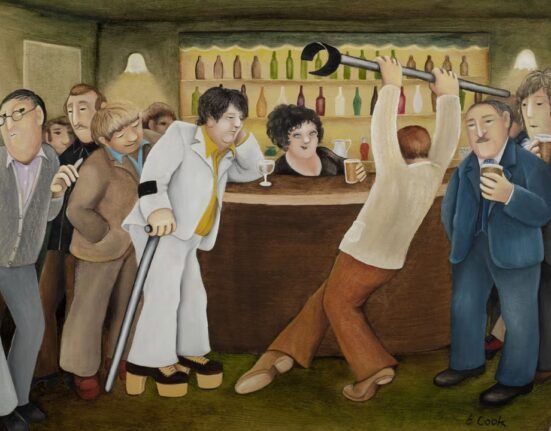

For more than two centuries, the only two pieces of evidence of the work’s existence were indirect. The first is the painting entitled Supper at the House of Nicolaas Rockox (1630-35). It belongs to the genre dubbed “wonder-rooms,” much sought-after by private collectors who wanted to display their accumulated wealth, via images that served as inventories. In this case, the key lies in the fact that in the center of the room — among other reproductions — one can see Rubens’s Samson and Delilah.

The second piece of evidence is a 1613 engraving of the painting made by Jacob Matham, a Dutch master printer. It was most likely commissioned by Mayor Rockox himself.

The painting’s reappearance

Samson and Delilah didn’t reappear until 1929, in Paris. It was then that a Rubens expert — the German art historian Ludwig Burchard — confirmed its authorship. It was a historic find in the art world. The problem, however, was that, upon the aforementioned expert’s death in 1960, it was discovered that he had appraised several fake Rubens to enrich himself.

In 1980, the National Gallery used its funds to acquire the work at a Christie’s auction. It paid £2.5 million (the equivalent of almost £11 million today, around $15 million). A mere trifle at today’s prices, but a record at the time, which grabbed headlines. Since then, the museum hasn’t been able to lift the curse that has surrounded the painting.

Let’s start with the revealing details that — according to the accusers — betray that the work is a forgery. The first — and perhaps the most striking, as well as the one that could most easily convince a layman — is Samson’s foot. In the painting exhibited at the National Gallery, the frame cuts off the toes from the giant’s right foot. Just like in amateur photos — where the framing is incorrect — and a hand or foot is also cut off.

In both Matham’s engraving and Francken’s canvas, the foot appears in its entirety. Hands and feet are extremely difficult to draw or paint, yet Rubens mastered these details, to the point of dedicating a work to the subject called Study of Feet. Hence, it’s strange that — with such skill — he chose to make the toes disappear, thus upsetting the balance of the composition.

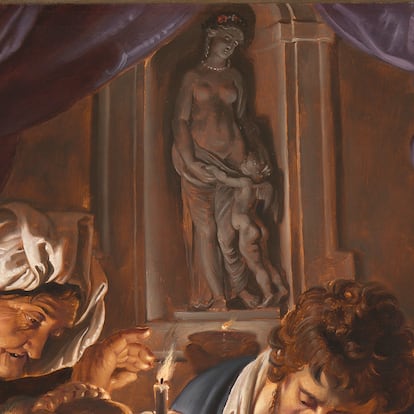

Then, there are other clues. In the upper left corner of the painting, for instance, there is a statue of Venus and Cupid. The brushstrokes appear crude, ill-defined, in a gray tone.

“Rubens even wrote a book in Latin, in which he explained his entire theory on how to paint statues: De Imitatione Statuarum,” Euphrosyne Doxiadis, the Greek art historian, explains. “And he always used ochre and earth tones, never black and white.”

In the background of the painting, on the right — as in Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656) — there’s a door. Five people contemplate the scene. One of them looks directly at the viewer, as if seeking complicity. In Matham’s engraving or in Francken’s painting, there are only three figures. This discrepancy would be further evidence of Doxiadis’s theory about the authorship of the work. For her, it’s clearly a copy.

According to the Greek art historian, the painting emerged from the group of disciples gathered in Madrid at the beginning of the 20th century, around the Post-Impressionist painter Joaquín Sorolla. Copying the classics was a good way to practice. And Rubens — due to his mastery — was a favorite among the students. For Doxiadis, the creator of the copy would have likely been Gaston Lévy, a collector and curator who ended his days in New York. However, in his youth, he learned from the Spanish painter.

To make clear the copy isn’t meant to deceive, the unwritten rule in the art world is to show some subtle difference from the original work that reveals the plagiarism. For example, a severed foot, or a knowing face looking at the viewer.

“We discovered Lévy’s name among Burchard’s notes [the German expert who confirmed the work’s authenticity in 1929] in 2000, among the National Gallery’s documents. ‘Purchased in Paris from the restorer Gaston Lévy,’ is what he wrote by hand,” Doxiadis details.

What’s more, the art historian asserts that the piece exhibited at the National Gallery isn’t an oil on oak — like the historic original — but rather a canvas glued to a board, which was later reinforced with another wooden board. She insists that museum officials have refused to use technology to refute her claim.

The National Gallery’s battle

The museum has dedicated years of work by its experts to confirm the authorship of its star painting and to silence what it considers to be baseless conspiracy theories. The National Gallery recently published an exhaustive report signed by three academics. It was led by Gregory Martin, one of the world’s leading experts on Rubens.

“This extensive study, conducted by our curatorial and scientific teams using the latest imaging and analytical techniques, provides compelling evidence in support of the painting’s authorship. It offers transparency around our research process and contributes meaningfully to the wider field of art-historical scholarship,” museum director Gabriele Finaldi wrote in The Guardian a few weeks ago. The British paper has also reported on the controversy.

While representatives of the National Gallery declined to speak with EL PAÍS, they sent the experts’ technical report to this correspondent.

Many specialists and critics have sided with the British art gallery and have defended Rubens’ authorship. In the art world — whenever evidence isn’t entirely conclusive — intuition, knowledge and imagination come to the fore. And it’s here that a painter mentioned at the beginning of this story reappears: Caravaggio. Perhaps he is the last key to understanding a painting that — due to its lines, use of chiaroscuro and execution — doesn’t appear to be by Rubens.

“Even when he’s imitating Caravaggio, Rubens can’t help being himself. The light is his, the candle glow is buttery and warm, like a pancake in an Antwerp kitchen. That mixture of southern sensuality and northern homeliness is another Rubens trait,” art critic Jonathan Jones writes in The Guardian.

“The quirkiness of this painting that gets some people’s goat — its cocktail of Caravaggio-ism and Rubens’s own carnal abandon — is actually a clue to its authenticity. What copyist would have been so subtle as to recreate this moment when Rubens takes on Caravaggio — especially in the earlier 20th century, when Caravaggio was not rated as he is today?”

Truth, like beauty, belongs to the eye of the beholder. And Samson and Delilah — like many other paintings — is eternally condemned to be an act of faith for its admirers, and an insult to its detractors.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition