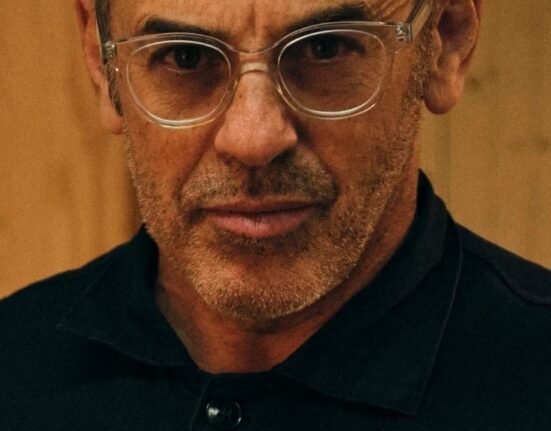

On a lazy afternoon in August, I met London-born artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley at Sybil, a self-described space for “weird gaming and speculative worlding” in the Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg. She was preparing for her most ambitious exhibition to date, THE DELUSION, set to inhabit Serpentine North Gallery during Frieze London through January 18, 2026. Like earlier offerings from the 30-year-old animator, filmmaker, painter, and performance artist, THE DELUSION is an immersive gaming experience anchored in archiving Black trans histories. Transforming the gallery into a haunted house-cum-game engine, Brathwaite-Shirley invites you into a new emotion-enhanced reality, one that asks for interpersonal engagement as you dive into quests. The parallel world—made largely by resurrecting defunct, forgotten technology—brings to life the artist’s own stories and feelings, the lives and co-writing of her direct community, and a landscape packed with horror, absurdity, and religious symbolism. In the words of Tamar Clarke-Brown, Serpentine Arts Technologies Curator and the lead curator on THE DELUSION, “no one is really doing what she is doing.”

THE DELUSION sits within a growing body of experimental work that pushes at the framework of gaming as art. “Only recently have art galleries and institutions been accepting that games can be seen as an art form,” the artist says. Her own work uses low poly aesthetics, referencing the grainy 2-D look of early ’90s first-person “corridor games,” and blends in images of friends—eyes, lips, and faces appear on legs, trees, and monsters—to bring to life a maximalist world where your interaction becomes the focus. Each piece preserves the words and lives of her community, often integrating group-workshopped memories into the plot, language, and visual details. These worlds center Black trans bodies, but they intentionally are not utopias. The Serpentine Galleries’ artistic director, Hans Ulrich Obrist, is quick to share that she is one of the most exhibited artists from the U.K. and from Germany of her generation, having shown at Fundació Joan Miró, the V&A, and The Tate Modern. “Her work has ramifications to both art in tech, but also to performance,” Obrist adds.

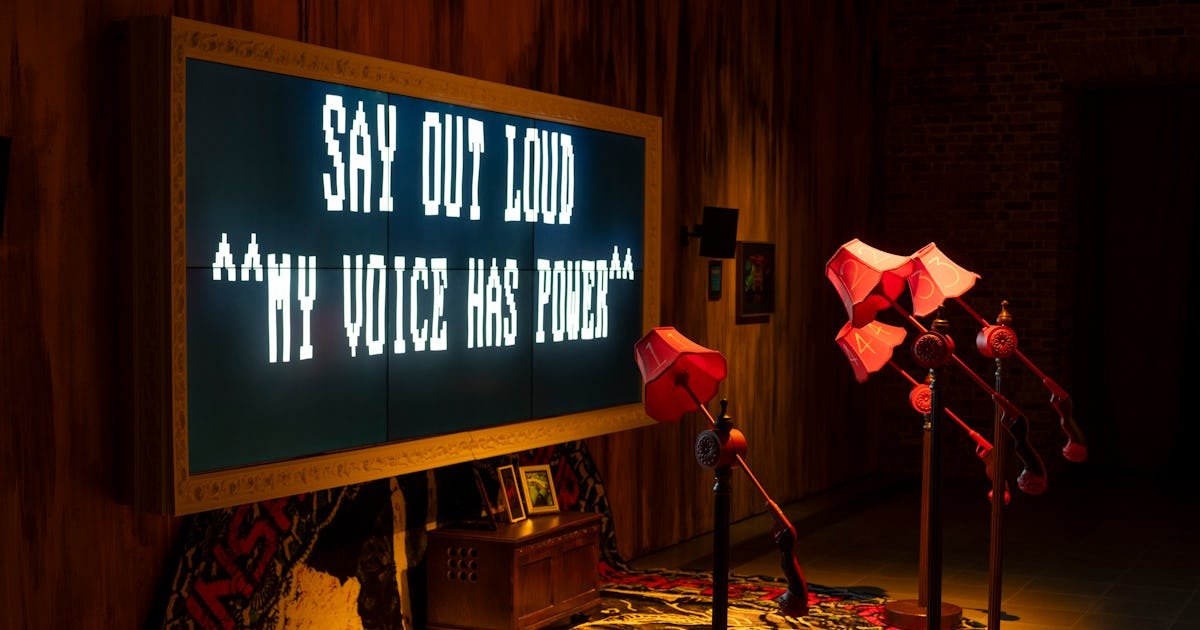

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, THE DELUSION, 2025.

Commissioned and produced by Serpentine Arts Technologies. © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Photo by Hugo Glendinning

Some highlights: In THE SOUL STATION (2024), Brathwaite-Shirley transforms the fabled club Berghain into an alternate universe where a revolution has abolished globalized slavery and visitors’ immediate moral choices dictate whether lives will be saved. Get Home Safe (2022) places the viewer at the helm of a horror arcade game, where they select their identity and are tasked with pressing choices on how to get a trans person home safe in desolate, late-night Berlin. In The Black Trans Archive (2020, blacktransarchive.com), one of the artist’s first pieces to catch widespread institutional attention, you are told, “THIS IS NOT YOUR SPACE. THIS IS OUR SPACE.” and “WE ARE HERE BECAUSE OF THOSE WHO ARE NOT.” You must accept the terms and conditions to enter. You may feel uncomfortable playing Brathwaite-Shirley’s archive-games, but your emotions are not being pushed aside here, rather they’re the central medium of her art. Crucially, she emphasizes, “YOU WILL NOT FEEL FORGOTTEN.”

“I’ve never seen anyone whose voice is so bold and so commanding, but also very unafraid,” says Clarke-Brown of Brathwaite-Shirley. “People are very used to editing themselves. The way she’s bridged the nerdiness of what she’s doing with wider cultural conversations and involving her community is a testament to the power of an artist to bring people into your vision, but allow their voices to also speak through the work.”

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, UNCOMFORTABLE HONESTY, 2024

© Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

The new commission at the Serpentine stems from a series of drawings Brathwaite-Shirley made reacting to things she witnessed on the news and online. “It’s like one massive icebreaker to get you to talk about three particular topics, which are dehumanization, censorship, and hope,” says Brathwaite-Shirley. “At the time, I was collecting a lot of hate comments and I had a hate article written about me. I had someone make a fake porn account,” she continues, explaining that after drawing around 100 sketches, “I wanted to write a story about how I feel like a lot of people who would consider themselves influencers use this mob of people as their intent rather than taking responsibility.”

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, BURNING DESIRE FOR HOPE, 2025

© Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

The story became Below the Blue Line, a graphic novel that grew into the world in which the game lives. Imagine: one day, every negative comment ever written online manifests all at once. “It doesn’t matter if the comment is impossible or very theological or theistic, or has dead people or monsters, everything just happens,” says Brathwaite-Shirley. People jump off cliffs and grow wings. Turn into creatures. Disappear and die. And the state reacts by getting rid of the Internet. The remaining population divides into tight factions that all think alike. “And if you don’t think the same, you’re instantly exiled,” says Brathwaite-Shirley. “Then propaganda takes on a religious [dimension]. To communicate, instead of going online, you access a global subconscious to try and place your propaganda in someone’s mind.”

The Serpentine is this global subconscious. Enter the Lydia Chan-co-designed house, partially inspired by the artist’s grandmother’s home, to play three games of your choosing, each motivated by a different heightened state. Lamps and doors become controllers, and require multiple people collaborating to really work.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, THE DELUSION, 2025.

Commissioned and produced by Serpentine Arts Technologies. © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Photo by Hugo Glendinning

The hope of THE DELUSION is to offer new tools for difficult conversations, which society often avoids while it is funneled content that continually re-affirms existing views. “I don’t care if it’s a good art piece. If people leave saying, ‘what a beautiful show,’ that would make me sad,” says Brathwaite-Shirley. “I guess that’s why I’m so unprescriptive about how you should play it. Because for me, playing means talking or shouting at it, like screaming, ‘fuck you, I hate that comment.’ I want the reactions to be honest. I want people to be able to be messy.”