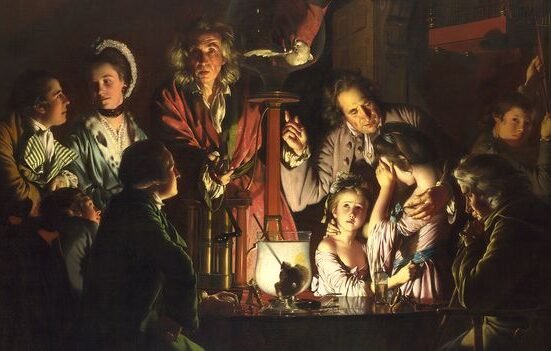

The exhibition’s curator, Christine Riding thinks that Wright developed his Caravaggio-like handling of light and dark because the London art world at the time was so competitive. “He was entrepreneurial and came up with a signature style. And I don’t think anyone dared do the same because he was so good at it – it became his USP.”

And while air pumps had been devised way back in 1650, the spirit of sharing scientific truths democratically was modern. “The dissemination of knowledge,” Riding tells the BBC, “was a new thing to the 18th Century.”

Depictions of modern life

And this brings us to the second ingredient of modern art – the representation of modernisations in society. Normally, this breakthrough is credited to pioneering artists in the 1800s such as JMW Turner.

Christine Riding believes that Wright’s innovation in this area was inspired by changing exhibition opportunities for artists in Britain at the time. Before the creation of a Royal Academy, artists had the choice of several competing display venues. One of them was the Society of Artists of Great Britain, where An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump was first displayed to the public. “The Society of Artists encouraged arts, science, and manufacture,” Riding says. “This was a world that didn’t tend to separate art and science, they tended to be seen as one and the same thing.”

Wright decisively exploited this new art scene and its encouragement of cross-disciplinary thinking. It inspired him to make science the subject of art. This also mirrored wider changes occurring in 18th-Century society, such as the Industrial Revolution, which was just beginning to gear into action in Great Britain, and whose epicentre was the Midlands, Wright’s place of birth. And Wright was clever enough to recognise the spirit of modernisation and record it for posterity.

He even knew some of the preeminent figures of this momentous era, including members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which met to discuss scientific and industrial innovation, and Richard Arkwright, the foremost entrepreneur of the Industrial Revolution.

So, Wright reflects a modern state of mind in An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump. Even contemporary critics recognised that Wright’s approach was significantly different to his artistic peers’. When the painting was first displayed, the Gazetteer called the artist “a very great and uncommon genius in a peculiar way”. We may raise an eyebrow at the word “peculiar” nowadays, but in the 18th Century it was meant to express extraordinariness.

But he did not necessarily match it with an extraordinary painting technique. His Caravaggio-like style was firmly of the 17th Century, like the air pump itself. This is a key difference with other artworks claimed as “modern” in the 19th Century. JMW Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844), for example, similarly depicted technological progress and its impact on society, but importantly, it also set forth a brilliantly innovative new way of depicting light, depth, smoke, steam and motion in oil paint.

And it’s this surrender of realism in exchange for expressionism and abstraction which is often claimed as a key feature of modern art, later to be innovated even further by such artists as Hilma af Klint and Kandinsky, and many others through the 20th Century and beyond.