An exhibition at the Ford Foundation Gallery captures how Black women artists mold clay and, through their labors, shape art history itself. Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art, which spans three generations of artists, begins with Ladi Dosei Kwali. Born in 1925, the artist created water pots between the 1950s and the ’70s in Abuja, Nigeria, connecting the intimacy of household vessels with the broader recognition of clay as an artistic medium. Each of the three water pots, produced from 1959 to 1962, is formed through a traditional coil method and then burnished, resulting in a soft, earthy sheen. In the first gallery, these objects are contextualized by archival photographs and publications documenting Nigerian pottery and Kwali’s career, underscoring how her practice was locally rooted and globally recognized.

Kwali’s unique process emerged from indigenous Gwari pottery techniques she learned in her youth. Later, at the Abuja Pottery Centre, she developed them into a distinctive blended style. There, she learned modern studio techniques — decorative glazing, modern kiln firing, and potter’s wheel experimentation — while remaining rooted in the tactile labor of hand-formed clay. As the first woman to study and thrive at the pottery training center, Kwali paved the way for Black women artists around the world to succeed.

The second half of the exhibition highlights ceramics created by the legatees of Kwali’s influence. Whereas Kwali entered the center as an already accomplished village potter, Halima Audu belonged to a younger generation of trainees. Her jar from 1959, with its dark, glossy glaze and sharply carved geometric patterning, demonstrates how she and others carried local hand-building traditions into a modern studio context. Displayed alongside it, Magdalene Odundo’s 1979 matte surfaced pot, accented with rounded cuts that echo the pot’s contours, integrates this lineage with a new sculptural language. Later works by Odundo, placed at the back of the gallery, showcase her signature tall-necked vessels featuring tilted rims that emphasize their bold silhouette and the play between curve and balance.

Contemporary artists such as Simone Leigh and Adebunmi Gbadebo follow in this tradition. Leigh cites Kwali and Odundo among the artists who inspire her ongoing practice as a sculptor. In the corner of the gallery, on the floor, sits Leigh’s domed “Village Series” stoneware sculpture (2023–24). The raised, plait-like surface evokes Black women’s braiding traditions, transforming the visual form into a monumental expression. Nearby, Gbadebo’s “Sam” (2023) is shaped from soil gathered at True Blue Plantation in South Carolina — where her maternal ancestors were enslaved — and edged with tufts of Black hair pressed into the pieces. The experimental pot becomes a memorial to land and body, inheritance and loss.

On the floor nearby are works from Phoebe Collings-James’s Infidel series (2025). Known for using clay to confront themes of vulnerability, refusal, and power, she presents tilted, abstracted figures with narrow necks and slanted mouths. Their fragile balance makes them feel both delicate and defiant.

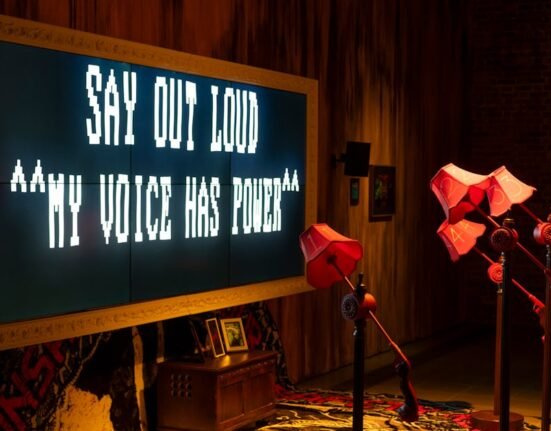

Nontsikelelo Mutiti’s graphic wall at the entry and exit presents a field of repeating geometric patterns that sets the rhythm of the exhibition. The design parallels the textured clay surfaces of the vessels, where ridges, grooves, and contours register the labors of the artists’ hands. These marks are not merely decoration but traces of process and presence — records of Black women’s expertise and experimentation with clay. Beginning with Kwali’s pots, through the works of Audu, Odundo, Leigh, Gbadebo, and other contemporary artists in the second gallery, the exhibition demonstrates how Black women’s ceramics embody continuity, carrying histories across generations.

Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art continues at the Ford Foundation Gallery (320 East 43rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through December 6. The exhibition was curated by Jareh Das.