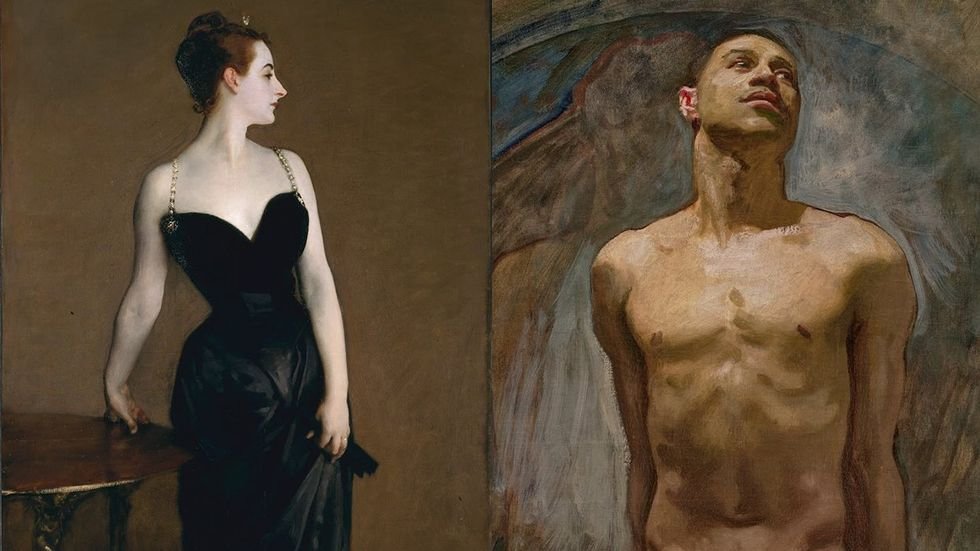

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

(from left) MADAME X 1884 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916; Nude study Thomas E. McKeller 1920 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (cropped)

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), the greatest painter of his generation and one of the best portraitists in art history, is having a moment. The exhibition “Sargent & Paris” is drawing crowds at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he has a cameo appearance in the new season of The Gilded Age.

In the show, the scheming Mrs. Russell (Carrie Coon) commissions Sargent (Bobby Steggert) to paint a portrait of her daughter, Gladys (Taissa Farmiga), hoping it will help secure the Duke of Buckingham (Ben Lamb) as a suitor. Though entirely fictional, the scenario is pitch-perfect. In an era marked by extreme wealth and social ambition, Sargent’s models used his portraits to assert their social standing, making him the official image-maker of the elite.

What distinguished Sargent’s work wasn’t just his technical brilliance but his uncanny ability to capture the sitters’ souls with a theatrical flair that makes them timeless.

Born in Florence to American expatriate parents, Sargent lived between Italy, France, England, and the United States, all of which turned him into a permanent outsider. A recent documentary about the artist, Fashion & Swagger, addresses the elephant in the room among art historians, Sargent’s sexuality. A lifelong bachelor, the film explores the queer markers in Sargent’s work, from his fascination with strong women, to how he chose the sitters’ attires and then manipulated them to heighten drama, to his depiction of male subjects with, at times, effeminate, gestures.

His close friend Jacques-Émile Blanche once remarked that “Sargent’s gay life in Paris and Venice was positively scandalous.” But if Sargent were indeed gay, as many now believe, he would have had to keep it hidden. He lived across the street from Oscar Wilde, whose infamous 1895 trials publicly cemented the association between artists and homosexuality. In that climate, with laws that broadened the criminalization of gay male activities, a public misstep could have destroyed Sargent’s career and reputation.

Yet, what makes Sargent so compelling is how he pushed the envelope by subtly flaunting his queerness and causing scandals such as the one surrounding his painting “Madame X,”

What follows are ten key moments, in life and on canvas, that reveal Sargent’s defiant queerness.

SARGENT’S INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP WITH FELLOW ARTIST ALBERT DE BELLEROCHE

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting \u200bPORTRAIT OF ALBERT DE BELLEROCHE

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

PORTRAIT OF ALBERT DE BELLEROCHE 1883, Private Collection

Recent scholarship suggests that Welsh painter Albert de Belleroche (1864–1944) may have been the love of Sargent’s life. They met in Paris and shared a studio while studying art, becoming inseparable.

Eight years Sargent’s junior, Belleroche had an androgynous beauty, with chiseled features and a delicate mouth that Sargent captured in intensely intimate portraits which advertise Sargent’s physical attraction. Their correspondence, in which Sargent addressed Belleroche as “Baby,” reveals a deep attachment which violated what were considered appropriate interactions between men at the time.

In 1883, Sargent painted a striking portrait of Belleroche and displayed it prominently in his dining room. It remained in his possession for the rest of his life. As Sargent’s grandnephew has remarked, “Anyone looking for Sargent’s sexual orientation will find it in his strong and obsessive studies of this handsome young man.”

THE REAL SCANDAL BEHIND SARGENT’S “MADAME X”

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b paintings \u200bMADAME X ALBERT DE BELLEROCHE IN PROFILE MADAME GAUTREAU DRINKING A TOAST

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

(from left) MADAME X 1884 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916; ALBERT DE BELLEROCHE IN PROFILE 1883 Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Miss Emily Sargent and Mrs. Francis Ormond; MADAME GAUTREAU DRINKING A TOAST 1883 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Sargent’s goal was to stand out at the 1884 Paris Salon, where 2,488 paintings, hung from floor to ceiling, competed for the attention of hundreds of thousands of visitors. His submission, titled Portrait de Mme ***, portrayed Virginie Amélie Gautreau (1859–1915), a glamorous figure in Paris’s high society, in a dazzling black dress that highlighted her unique profile and lavender skin tone. The plunging neckline and a jeweled strap slipping off her shoulder, suggesting she wore no undergarments, caused a riot-like scandal with widespread media coverage and caricatures mocking it.

What started as a calculated provocation concocted by two outsiders seeking recognition in Paris clearly backfired. Devastated by the uproar, Sargent repainted the strap and fled to London seeking a fresh start with a new clientele. Despite the criticism, Sargent kept the painting until he sold it to the Met in 1916, when he insisted on the title Madame X, calling it “the best thing I’ve done.”

But, beneath the famous scandal lies a deeper and rarely discussed transgression. Albert de Belleroche did at least 80 sittings as a model for Madame X. One of his portraits is clearly the basis for Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast (1883). Blending the features of Gautreau, his public muse, with Belleroche, his private obsession, Sargent slyly defied gender conventions. In doing so, he echoed one of his idols, Michelangelo, whose figures in the Sistine Chapel often fused male and female forms.

THE SHOCKING NUDE PORTRAIT OF SARGENT’S BLACK MUSE, THOMAS MCKELLER

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting \u200bNude study Thomas E. McKeller

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

Nude Study of Thomas E. McKeller 1920 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The ravishing Nude Study of Thomas E. McKeller (1920) is one of Sargent’s most arresting works. In a provocative departure from his society portraits, McKeller appears completely nude, his genitals a focal point, his tilted head captured in ecstasy.

The story begins in 1916 when, tired of being typecast as the elite’s portraitist, Sargent accepted a commission to paint the murals for Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Sargent, who was 60 at the time, struck a conversation with Thomas McKeller, a hunky 26-year-old Black elevator operator, and asked him to become his model on the spot.

During the following years, Sargent transformed his Black muse into alabaster-white gods and goddesses for his murals. Surprisingly, Sargent featured McKeller’s irregular left nipple in many of them, making his identity hauntingly present.

Nude Study of Thomas E. McKeller was one of his most beautiful portraits. But Sargent never exhibited it publicly, though he proudly displayed it in his studio. For Trevor Fairbrother, one of the leading scholars of Sargent’s work, this portrait serves as compelling evidence of the artist’s queer desire.

McKeller’s great-niece recently suggested that McKeller may have been gay. We’ll never know if they had an intimate relationship. In any case, this portrait will forever act as a coded love letter that defies time, taboo, and erasure.

THE SUBLIME PORTRAIT OF SARGENT’S CRUSH, DR. SAMUEL POZZI

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting \u200b\u200bDR POZZI AT HOME

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

DR POZZI AT HOME 1881 Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

John Singer Sargent had a talent not just for painting, but for choosing sitters who stirred publicity. The charismatic Samuel Jean Pozzi (1846–1918) was a renowned gynecologist and one of Paris’s most notorious men, famous for his constant flirting with men and women, including a rumored affair with Madame X no less.

There’s no doubt that Sargent was infatuated with Pozzi, who embodied Sargent’s favorite type, dark Mediterranean men. Sargent’s painting exudes sensuality and challenges portrait tradition by showing Pozzi in bedroom attire, wearing a “passion red” robe against a lush velvet curtain.

Sargent highlights Pozzi’s handsome face and direct gaze while one hand tugs lightly at his belt, as if caught in the process of disrobing, with the tassel hanging provocatively below his groin.

But Sargent does more than eroticize; he subtly queers the composition. Pozzi’s hand on his waist in the contrapposto pose is associated with queerness. His white collar and cuffs, cinched waist, and elongated, expressive hands blur the lines between masculine and feminine. The final result of his audacious composition leaves you breathless.

SARGENT’S NUDE PORTRAITS OF HIS VALET AND CLOSE COMPANION, NICOLA D’INVERNO

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b paintings NICOLA D’INVERNO NICOLA D’INVERNO READING

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

(from left) NICOLA D’INVERNO NATIONAL MJSEUM AND GALLERIES OF WALES, CARDIFF; NICOLA D’INVERNO READING READING PUBLIC MUSEUM

Nicola D’Inverno was a 19- year-old dashing amateur boxer when he showed up at Sargent’s door in 1892 offering to model for him. Sargent asked him in to see his physique. He must have liked what he saw, because Nicola became not only Sargent’s model but his valet, studio assistant, photographer, masseuse and travel companion.

In an article after Sargent’s death, Nicola said, “I was the very man Sargent wanted.” He was right, Nicola was Sargent’s exact type. Sargent even paid for Nicola’s gym fees so he remained fit.

Sargent painted many portraits of D’Inverno. One particularly tender work shows Nicola reading in bed, an unusually intimate depiction, which shatters the rigid master-servant dynamics of the era. A watercolor from a trip to the Canadian Rockies captures their shared space in a tent, an unmistakable nod to same-sex intimacy.

But it’s in the secret trove of male nudes, many featuring D’Inverno, that Sargent’s private desires become most transparent. These works, never exhibited during his lifetime, surfaced only after his death.

In a particularly subversive 1900 study, D’Inverno reclines in the pose of an odalisque, an erotic posture historically reserved for female subjects, here reclaimed with same-sex desire.

Completely devoted to Sargent, whom he called “the greatest man he ever knew,” D’Inverno remained at Sargent’s service for 25 years, until he had a fight with a Boston bartender and Sargent dismissed him from his staff.

SARGENT’S COUNTLESS HOMOEROTIC MALE PORTRAITS

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b paintings \u200bMAN WEARING LAURELS and YOUNG MAN IN REVERIE

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

(from left) MAN WEARING LAURELS Los Angeles County Museum of Art; YOUNG MAN IN REVERIE 1876 The Hevrdejs Collection

One of the most compelling and overlooked aspects of Sargent’s work is the overt homoeroticism that permeates many of his male portraits, which art historians are prone to dismiss.

The exquisite “Young Man in Reverie” (1876) and “Man Wearing Laurels” showcase, once again, Sargent’s attraction to rugged, Mediterranean, working-class men. This painting’s title invokes respectable classicism but the overwhelming erotic charge in the man emerging from shadow leaves no doubt about Sargent’s true intentions.

Sargent’s sexual interests were hardly a secret among his friends. One of his sitters remarked that the artist had a weakness for Venetian gondoliers, who were known for being amenable to the advances of wealthy male travelers. Sargent painted many of them with a sultry gaze. He even referred to his trusted valet Nicola D’Inverno as “my gondolier.”

SARGENT’S DARING “GANG BANG” MURALS

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b paintings \u200bHELL HERCULES FIGHTING THE HYDRA ORESTES

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

HELL BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY (top); HERCULES FIGHTING THE HYDRA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS BOSTON (bottom left); ORESTES MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON (bottom right)

By 1916, John Singer Sargent had grown weary of his reputation as society portraitist. Seeking artistic freedom, he accepted the commission to paint the murals for Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Here, liberated from society’s corset, Sargent indulged in mythological themes that gave him license to paint what he truly loved, the nude male body, without any fear of pushback.

Two of these murals, Orestes Pursued by Furies and the phallic Hercules Struggle with a Hydra, can easily be interpreted as a metaphor of Sargent’s struggle with his sexuality.

Sargent also worked for 30 years in murals for Boston’s Public Library. Among its most infamous panels is Hell, a writhing mass of interlocked male bodies. When Andy Warhol first laid eyes on it, he famously quipped: “That’s not hell — that’s a gang bang!”

SARGENT’S QUEER AND GENDER-NON-CONFORMING CIRCLE OF FRIENDS

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting \u200bPORTRAIT OF VERNON LEE

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

PORTRAIT OF VERNON LEE 1881 Tate

Though famously discreet in public, Sargent was known to let loose among his inner circle, many of whom were queer. One close friend recalled that during these private gatherings, “Sargent’s favorite expression was ‘Lala!’” and noted that “he was very gay all the time.”

Among this chosen family was the unconventional Vernon Lee (1856–1935), the pen name of Violet Paget: a pioneering feminist, art historian, and writer who rejected the era’s rigid gender expectations. Her masculine pseudonym and androgynous style were key to her public identity. Sargent captured both in his lifelike 1881 portrait of Lee, which she boasted “represented her true self, fierce and cantankerous.”

Lee, who opposed being labeled a lesbian, lived openly with Clementina Anstruther-Thomson (1857–1921) as lovers and coauthors. Sargent also painted her portrait.

SARGENT’S DANDY PORTRAIT HAS BECOME A QUEER ICON

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting PORTRAIT OF W GRAHAM ROBERTSON

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

PORTRAIT OF W GRAHAM ROBERTSON 1894 TATE

Sargent painted multiple portraits of dandies, who were connected to Oscar Wilde and came to symbolize homosexuality at a time when queerness was criminalized.

Sargent was attracted and repelled by the idea of the exhibitionist dandy, a persona he wouldn’t allow himself to be. In an artistic wink, he portrayed dandies with a hand on their waist as a code to reveal the queerness in others that he may have withheld about himself.

One of the most famous examples is his 1894 portrait of W. Graham Robertson, a prominent members of Wilde’s queer circle. Sargent pursued him relentlessly until he agreed to pose. In his autobiography, Robertson campily quips: “Why the great artist would be interested in a young man with blonde hair and blue eyes, I cannot imagine.”

Sargent selected an exquisitely tailored coat so tight and warm that Robertson nearly fainted under the studio lights. In a moment full of the kind of drama Oscar Wilde thrived on, Sargent had to grab Robertson by the lapels and rush him outside for air.

Walking a fine line between mockery and homage, Sargent fills the portrait with queer codes, including a poodle with a yellow ribbon, a detail that sent London society into gossiping frenzy.

THE SEXUALLY REVEALING MALE NUDES

JOHN SINGER SARGENT\u200b painting

Original artwork by JOHN SINGER SARGENT

NUDE MAN LYING ON A BED 1917 PHOTO BY AUTHOR

After John Singer Sargent’s death, a cache of male nudes emerged in which a restrained homoeroticism gave way to blatant sexual titillation.

A striking example is Nude Man Lying on a Bed (1917), which features a naked young man sprawled across rumpled sheets and smoking a cigarette, an obvious post-coital pose that museums typically omit in their descriptions.

In these male nudes, Sargent finally allowed himself to paint desire, not veiled, not coded, but open, unguarded, and disarmingly real.

The full story of Sargent’s sexuality remains elusive, in part because many of his personal letters were destroyed to preserve his reputation. Rather than rely on the tired trope of Sargent as an “asexual bachelor married to his work,” I align with his biographer Trevor Fairbrother, who argues that “the tension between Sargent’s public persona and his repressed sexuality is the engine that drives the emotional and erotic undercurrents in his work.”

In essence, John Singer Sargent’s queerness is what gave America’s Gilded Age the appearance of royalty. If you have any doubts, just check with Mrs. Russell, who, thanks to Sargent, was able to land the Duke of Buckingham after all.

Ignacio Darnaude, an art scholar and lecturer, is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art. You can view his Instagram, lectures and articles on queer art history at linktr.ee/breakingthegaycodeinart

This gallery was assembled by equalpride’s digital photo editor, Nikki Aye.

This article originally appeared on Out: The Gilded Age to a ‘gang bang’: John Singer Sargent’s defiantly queer art