Cork Street, the beating heart of Britain’s commercial art world, for much of the past century, celebrates its centenary this year. To mark the occasion, 15 galleries are taking part in a group show inspired by a controversial Jean Cocteau work that the American dealer and patron Peggy Guggenheim was forced to install out of public view, at the back of her Cork Street gallery in 1938.

Labelled obscene by the British authorities for its depiction of nudity and pubic hair, La peur donnant des ailes au courage (fear gives wings to courage) was confiscated upon arrival in the UK. It was only through incessant petitions to the government from Guggenheim and her adviser, the artist Marcel Duchamp, that the work was eventually released on the condition that it would be shown in a back office of her gallery, Guggenheim Jeune, which occupied the second floor at 30 Cork Street.

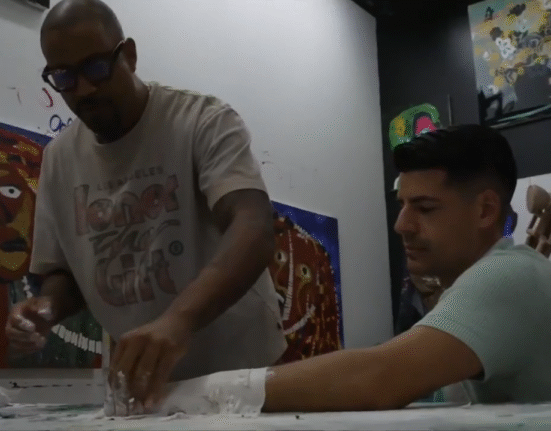

Still from Shirin Neshat, Roja (2016)

Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery

Today, all 15 galleries on the Mayfair thoroughfare are presenting exhibitions that pay homage to the unabashed spirit of Cocteau’s work, as well as Guggenheim’s belief that dealers must uphold and encourage artistic practices, even in the face of societal and political pressures. Stephen Friedman Gallery is showing photographs by Caroline Coon alongside ceramics by Cocteau, while Alon Zakaim Fine Art is exhibiting Impressionist artists who initially faced intense criticism and rejection from their contemporaries. Goodman Gallery is presenting Shirin Neshat’s film Illusions & Mirrors—a work that “embodies the ongoing role of art as an act of defiance and resistance”, according to the gallery’s senior director Jo Stella-Sawicka.

It is an unprecedented move for so many major galleries to work together on a single exhibition—but it also sums up the renewed collaborative spirit on Cork Street, which has weathered several storms as the art market has cycled through periods of boom and bust over the past century. During the past few years, several heavyweight contemporary art galleries including Goodman Gallery, Stephen Friedman, Tiwani Contemporary and Alison Jacques have moved in, re-cementing the street’s position as a vibrant, vital art hub in the UK capital.

“We’ve had full occupancy for the past three years, and things have really come back. There’s footfall on the street and a sense of community. It feels like we’re really building something now,” says Jacob Twyford, a director at Waddington Custot gallery, which was first established as Waddington Galleries by the Irish art dealer Victor Waddington and his son Leslie on Cork Street in 1958. Leslie Waddington joined forces with Stéphane Custot in 2010 to create Waddington Custot.

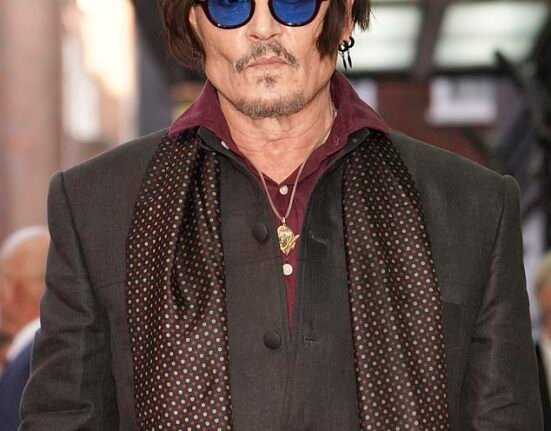

Installation view of Peter Blake at Waddington Custot

Courtesy of the artist and Waddington Custot

Contrary to its image for being stuffy and old fashioned, Cork Street’s history includes its fair share of scandal, as well as being a place where avant-garde art was shown long before it was accepted by the mainstream art world.

The story begins in 1925 when Fred Mayor opened Mayor Gallery, which quickly developed a reputation as a forward-thinking space, showing artists including Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, Paul Klee and André Masson in Britain for the first time. In the years before the Second World War, the street became a hotspot for Dada and Surrealist art, not least at Peggy Guggenheim’s short-lived gallery, which closed after just 18 months due to financial losses and the impending war. After the war, newcomers included Piccadilly Gallery, Browse & Darby and Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

In 1985, the trailblazing contemporary art dealer Victoria Miro opened on Cork Street, at a time when very few galleries or museums supported contemporary art in London. Earlier that year, the punk artist collective The Grey Organisation had thrown grey paint over the windows of Cork Street galleries in protest over the snobbery of the art world elite.

Waddington Custot, then Waddington Galleries, set up on Cork Street in 1958

Courtesy of Waddington Custot

It was the same year Twyford joined Waddington Galleries as a technician. “I didn’t realise it at the time, but I joined right at the start of the boom years that went through the late 1980s—the art world was just going mad,” Twyford recalls. At that time, Waddington Galleries occupied no fewer than six spaces on Cork Street. “We were this huge organisation with 56 employees. We were the first of the big, super galleries back in the day.”

Twyford says the biggest difference with the art world back then was that it was far more localised. “Leslie Waddington was the king of Cork Street and Arne Glimcher was the king of 57th Street,” he says. “People used to travel to see galleries. There wasn’t an art fair opening near you anytime soon.”

Market crash

Fortunes rapidly changed after the economic crash of the early 1990s. “Everything came tumbling down,” Twyford says. Unlike the current market slowdown, “it was a cliff edge in 1990”, he adds. “It just stopped. It wasn’t that pictures that had been worth whatever were now worth half a million, you just couldn’t sell them at all. It became very, very difficult. It took us six or seven years to trade our way back out of the losses that were made at that time.”

Around the same time, the commercial art market began to look east. Maureen Paley had led the charge a few years earlier, and in 2000, Victoria Miro relocated to a former furniture factory in Hoxton.

Twyford thinks the period marked a “death knell” for a way of dealing where galleries traded a mixture of secondary and primary market works. “The galleries that then gathered steam were run on a very different model, where it was pretty much 100% primary market,” he says. “They wanted big, more urban, gritty spaces to match the contemporary art they were showing so they all moved out to Hoxton. People shut up on Cork Street and it became a very quiet, sleepy place.” Waddington Galleries drew in its horns and consolidated its spaces to 11 and 12 Cork Street, where it remains today.

The doldrums

Cork Street took another hit in 2012 when landowners the Pollen Estate gave notice for at least half a dozen galleries to leave under plans to build luxury flats in their place. While some galleries including Bernard Jacobson did relocate, plans were re-evaluated after staunch opposition from the art world. The building works that eventually went ahead left the street “a dust bowl”, Twyford says.

That lasted until around 2017 when Cork Street reopened. “It was another curious period of time when there were eight gallery spaces to let on the street,” Twyford says. “Although the spaces were rentable, there was all the negotiation that involved persuading people to come back to Cork Street after a long hiatus.” Lisson Gallery, among others, temporarily took up spaces as the art world grappled with the pandemic.

Installation view of Balancing Acts at Holtermann Fine Art

Courtesy of Holtermann Fine Art. Photo: Ollie Hammick

The Norwegian-born dealer Marianne Holtermann was one the galleries to move in during this period, taking up her space in 2019 at 30 Cork Street, the address formerly occupied by Peggy Guggenheim. “The street was pretty empty at the time,” she recalls. “It felt a bit like, who’s going to come down Cork Street? But of course, people have come.” Holtermann is showing a diptych by the Cuban painter Michel Pérez Pollo as part of the centenary show; his work, the dealer says, fits into the theme for feeling “a bit precarious and off kilter”.

Today, the 15 galleries on Cork Street—which include the space at number nine managed by Frieze Art Fair—are weathering the current market turbulence together. “What we’re doing as a community of galleries is trying to rekindle that sense of something special—a reason why you’d want to spend three or four hours in Cork Street,” Twyford says. “People are not just shopping for objects anymore, they’re shopping for experiences, and it’s up to us to make each gallery visit a unique experience.”

As part of the group exhibition, Waddington Custot is showing works made by Peter Blake over the past six or seven years. “People often refer to Peter as a pop artist, but if I had to give him a label, I’d call him a contemporary folk artist because he’s always commenting on his time. Even though he’s now 94, he’s as contemporary as he was when he was 24,” Twyford says. “And he’s been alive for almost as long as Cork Street as we know it, which felt appropriate.”