When Emilie Gordenker took over as director of Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in 2020, she hoped to organise a show spotlighting the German artist Anselm Kiefer’s enduring admiration for the Dutch master. She teamed up with the Stedelijk Museum nearby and approached Jay Jopling of White Cube, one of Kiefer’s galleries, for advice. “He was really keen on the idea,” says Edwin Becker, chief curator of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum.

What started with a single curatorial vision was realised through a collaboration between two institutions, the artist’s studio and his London gallery. The resulting display ran at the Dutch museums this spring and brought together monumental new canvases, as well as other paintings, drawings and films spanning Kiefer’s entire career. At the Van Gogh Museum, his works were placed near those of the artist who inspired him. The show opens in a smaller version at the Royal Academy in London on June 28.

What role did White Cube play in putting the show together? “They were a tremendous help for us,” says Becker. When the curatorial team was searching for a vitrine paying homage to Van Gogh that Kiefer had made for the Rijksmuseum in 2010, White Cube tracked it down to Shanghai. “We realised it would be too expensive to ship it to Amsterdam,” says Becker, “so they helped us to ask Kiefer if he would make a new one for our show.” (He did.) “White Cube played a crucial role connecting us to the artist and his studio and helping us with so many questions: ‘Would Kiefer like this or that?’, ‘Will he do interviews?’, ‘How should we market this exhibition?’” The gallery also made a contribution towards the cost of the Dutch catalogue and towards the Royal Academy for the London version of the show, though it declined to say how much it provided.

As museums struggle with declining government money and navigate an increasingly tough fundraising climate, the support of commercial galleries in organising exhibitions of artists they represent has become more important than ever. On the funding side, galleries typically help institutions with the costs of producing catalogues and shipping art and by underwriting dinners held to mark the opening of shows.

“When a museum decides to do a contemporary art show, their first call is always to the artist’s gallery,” says Emily Tsingou, a London art adviser. “Since the pandemic and the spike in oil prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the expenses of staging a show have become enormous; it now costs $3,000 to crate and transport just one medium-sized painting from the United States to Europe, one way. Institutions are under tremendous pressure to raise money to cover these charges.”

But critics warn that it is problematic for museums to rely on money from galleries that have a financial interest in an artist’s success. Veteran art dealer David Juda is one of them. “One of the dangers is that museums are more likely to show an artist if they know they can get financial support from galleries. If an artist doesn’t have gallery backing or powerful collectors, museums are less likely to show them and that’s wrong. Conversely, if a wealthy gallery can pay for everything, a museum might be tempted to organise a show that isn’t that good.”

The system undoubtedly privileges artists represented by the biggest, richest galleries. “Artists want to work with the likes of Hauser & Wirth, Gagosian and David Zwirner precisely because these galleries can support museum shows; artists want to see their work displayed alongside the Old Masters,” says a senior source close to museum and galleries who asked not to be named.

Concerns about museum reliance on the commercial sector were once widespread. When Charles Saumarez Smith joined the V&A in London as assistant keeper in 1982, “staff were not allowed to have meals with dealers. The official view then was that the public and private sectors should not interact. Of course, that was a time when institutions were not fundraising as they are today.”

The subsequent decline in public subsidy for museums ramped up pressure on institutions to increase earned income and find private money, leading to increased reliance on commercial galleries and other sponsors. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s core funding for cultural organisations decreased by 18 per cent per person in real terms between 2009 and 2023, according to a 2024 report by the University of Warwick and Campaign for the Arts.

Throughout this time, museums remained keen to assert their curatorial independence, says Saumarez Smith, who served as secretary and chief executive of the Royal Academy from 2007 to 2018, after leading the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery.

“At the RA, the decisions on whether to do a show were always taken on artistic grounds; then we would scramble to find the funding . . . What was taboo in museums was talking about the issue before choosing to do a show, because of the anxiety of seeming beholden to commercial galleries; this is still true today. It’s a bit artificial: if you need the support of a dealer, you might as well be upfront about it.”

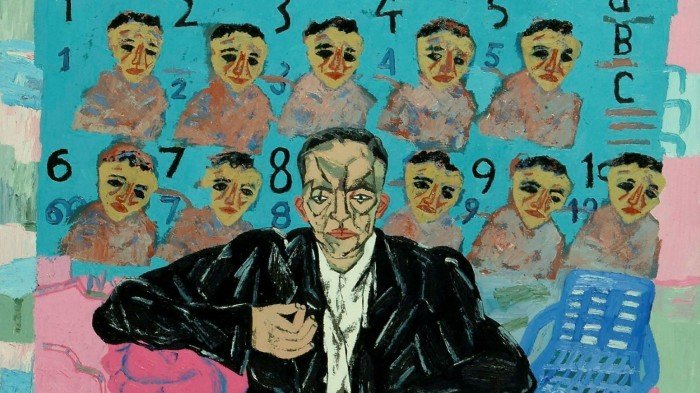

Beyond the funding they provide to museums, commercial galleries are also able to introduce institutions to collectors of a particular artist’s work who may lend their art for display and give money towards exhibitions. The Serpentine Galleries’ current survey of the Indian modernist Arpita Singh (to July 27), the 87-year-old’s first solo institutional show outside her native country, features 160 works, with 139 of these on loan from institutions and private individuals in India, including Kiran Nadar, who is building a vast museum in New Delhi for her expansive art holdings.

Vadehra Art Gallery in New Delhi, which has worked with Singh for nearly 30 years, helped the Serpentine to identify these collectors and then set up introductory meetings with them, Roshini Vadehra says in an email. Vadehra also arranged visits to the artist’s home and studio for Serpentine curator Tamsin Hong and artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist. “Arpita doesn’t check email, so we co-ordinated the encounters.” Finally, Vadehra loaned several works from her family’s collection to the London show and provided the Serpentine with high-res images of some of the works.

“Galleries have long relationships with their artists,” says Rachel Lehmann of the New York gallery Lehmann Maupin, which helped Tate Modern with its current survey of the work of South Korean artist Do Ho Suh (to October 19) and paid for the shipping from New York of an installation included in the show. “We can provide all the information needed with the archive, the location of works, details of how to approach a collector who may loan the work and sometimes, as is the case with this particular show, give museums ideas of which cultural institutions might provide funding.”

There is a commercial upside for galleries’ support of museums. The prestige of an exhibition in an important institution can buoy an artist’s market and galleries capitalise on this by staging concurrent shows or offering work at art fairs. On June 25, White Cube opens a selling exhibition of paintings made by Anselm Kiefer in the last six years at its Mason Yard’s space to coincide with the artist’s Royal Academy show while Lehmann Maupin is offering new works by Do Ho Suh at Art Basel this weekend.

“Galleries are not charities and they are struggling at the moment, just like museums,” says Tsingou. “The art world is an ecosystem and we all need to support one another otherwise the whole system will come crashing down. As long as museums maintain curatorial independence, I don’t see what the problem is.”

For museums prepared for the slog, though, it is still possible to organise displays without the support of the commercial art world. The current exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery of work by the British-Pakistani artist Hamad Butt (to September 7) is the second of three exhibitions devoted to artists who have no commercial gallery representing them or their estate (the other two are Donald Rodney, which closed in May, and Joy Gregory, which opens in October). “We’ve done this in the face of the odds,” says Whitechapel director Gilane Tawadros, who co-curated the Hamad Butt exhibition. “It has been difficult, extremely difficult.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning