I’ve been raising funds for a building project: not a hospital, not a school, but an arts centre.

It’s not an easy sell at the best of times but add in a pandemic and the fact that I’m in Africa and, according to the current rules of financial engagement, art is the very lowest of priorities.

According to the people who decide these priorities, art does not create thousands of jobs, or keep people from dying, and it doesn’t “scale up”.

I used to work in development, so I understand where this mindset comes from, but now that I have worked in arts and culture, I see repeatedly how much Ugandan society misses out on because we do not prioritise our art.

Artists make us constantly question how we see the world. Sometimes, they help us imagine a new one. As an arts centre, one of our greatest legacies is our residency programme. During a residency an artist will come for a few months, be given a studio, living expenses, a modest materials budget, and access to our community and our library of contemporary African art.

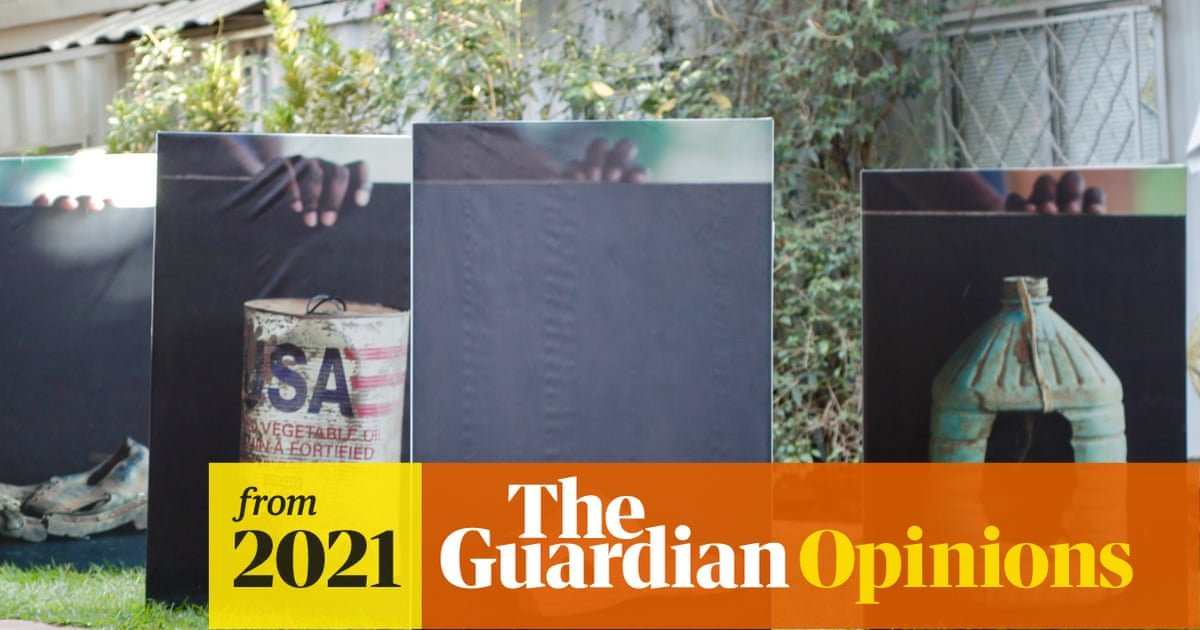

The work of one of our previous artists in residence generated conversations around anxiety and depression. Another, Bathsheba Okwenje, used her residency to represent the interior lives of people fleeing from conflict to look at the politics of migration and return.

The only expectation of our artists is that they make the most of this time. No pressure to make work for a grand exhibition, or an established market – just come and try new things. Explore, experiment, fail and try again. No one has to prove anything, just share the experience with others during an open studio at the end of the residency. This is especially powerful in Uganda, where artists are constantly receiving the message from the government – at school and in their own homes – that art does not matter.

Even when art is clearly, and measurably, bringing in thousands of jobs and millions of dollars to the region – through events such as the Sauti za Busara music festival in Zanzibar and Uganda’s Nyege Nyege festival – organisers still need to hunt hard continually for funding. Lawmakers in east Africa keep introducing bills to tax digital content creators; Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, is on record as saying arts courses are useless.

As an artist in Uganda, your family won’t stop sending you job applications to work at the local bank. So for creative people to have a space where they can meet and connect with others who may or may not be like-minded, where differences are met with curiosity, is a rare and valuable thing.

So how to raise funds for an arts centre in such a climate? Our dream is not to rely on the current funding paradigms at all, but through the centre generate our own income to feed back into our programming. But we have to first build the centre, and any African organisation asking partners for money needs to fit into a particular narrative.

We are often eligible for grants because of our status as a non-profit organisation in a developing country and yet none of these grants engage critically with the very notion of what development even means.

I have read many promising funders’ stipulations only to get to the fine print that says, “we don’t fund projects whose primary aim is the institutional development of the organisation itself” or “we don’t fund infrastructure or capital projects”.

The message here is that if we want the money, we should fit the mould they have made. If partners want to scale up, find a programme that works with 1,000 artists in a year. If they want job creation, we “provide capacity building to self-employed creatives upskilling them to thrive and grow the creative economy”.

Development for whom, according to whom, into what, and at what cost? This month our governments celebrated the signing of the east African crude oil pipeline agreement between Tanzania and Uganda at a time when our climate faces crisis and our planet is on fire.

Uganda grants sugar companies licence to clear mature forests on the one hand, while receiving million-dollar loans to plant forests with the other. Artists draw the connections between these issues in a way that policy does not. Through art, pressing issues such as development, racism, the climate crisis, gender equality and LGBTQ rights are confronted in ways that lead to assumptions being questioned. The art world is by no means a utopia and can be problematic, cynical and harmful too, but it is one of the few areas where we collectively engage with what utopia even means.

With the pandemic, we have witnessed the failures of the status quo, but continue to invest in the same values that have let us down. People say that now is the time to reimagine new structures but there remains no investment in that imagination. Yes, we need more hospitals, more jobs and better roads, and we also need to prioritise alternative ways of doing – and of being. That is art.

Ugandan imaginations – and African imaginations – are worth investing in.