Two heads are proving better than one this year at Art Basel Paris, where there’s a record number of galleries splitting booths. While shared stands have been cropping up intermittently at fairs over the last several years, the increasing concentration of them reflects a shifting art market and changing business practices.

“It’s not particularly novel, we’ve done joint booths before at fairs, but there is certainly a growing interest in it,” said Jeffrey Rosen of Tokyo’s Misako and Rosen, who is sharing a stand with Lambdalambdalambda of Pristina, Kosovo. The gallerists have been working together on projects since 2019, when they and Park View/Paul Soto of Los Angeles launched La Maison de Rendez-vous in Brussels; the collaborative exhibition space ran through 2023.

Rosen said that, having run the gallery for more than 10 years at that point, he wanted to find a “mutually supportive, non-competitive manner” of mounting exhibitions with a curatorial focus, adding that buddying up “ultimately came down to a matter of survival.”

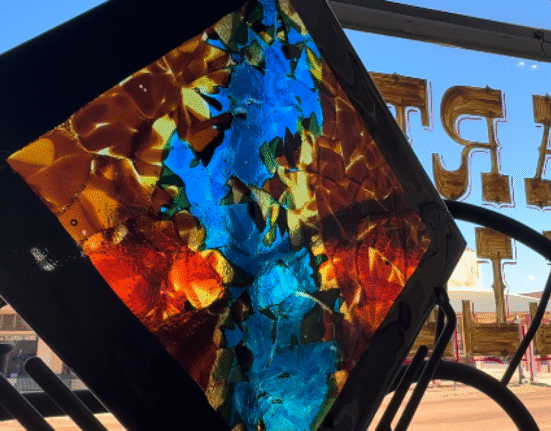

Misako and Rosen’s joint booth with Lamdalamdalamda at Art Basel Paris 2024. Photo: Margaret Carrigan.

At Art Basel Paris, which opened today to VIPs at the Grand Palais in Paris, the front of their shared booth features a textile piece by Hana Miletić (around $20,000) brought by Lambdalambdalambda, and an angular graphite and wood work by Naotaka Hiro, from Misako and Rosen. Priced at €40,000 ($43,500), it had already sold by lunchtime on the VIP day. At the center of the booth was a large text work by Nora Turato for €75,000 (roughly $80,000). The pair is also launching a private works-on-paper show in a residential space this week, with an eye toward opening a more permanent space in Paris in the future.

Isabella Ritter of Lambdalambdalambda said that “it seems more interesting to work with than against one another,” especially given that her gallery is not located in a major art world destination. “Partnering allows us to offer a more global picture,” she said, adding that it’s helpful to work with someone “who you trust and who has a similar sense of what collaboration means.” She has also previously shared booths with peers at Fiac in Paris, as well as L.A.’s Hannah Hoffman Gallery at Frieze Los Angeles.

Rising Co-Representation

Jointly representing artists has become increasingly commonplace among galleries in the last several years, and the growing number of shared booths at art fairs may be a reflection of this trend. Hoffman is again splitting a booth, this time with Candice Madey from New York. Together, they have brought two dozen works by the American artist Darrel Ellis; the two dealers have co-represented Ellis’s estate for several years.

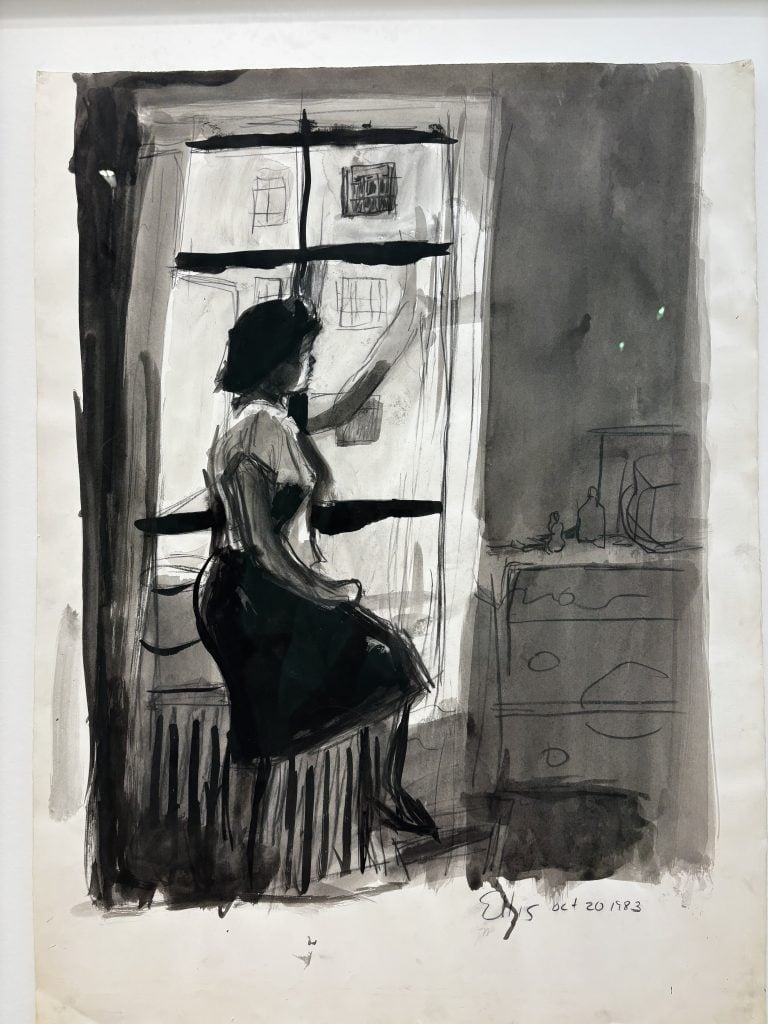

The artist, who died in 1992, is known for his photographs and drawings exploring Black and queer life in the 1980s. He’s been the subject of a traveling U.S. museum show that culminated at the Columbia Museum of Art in South Carolina earlier this year, from which many of the works at the booth—priced between $10,000 and $45,000—are drawn.

Madey said bringing his work to Paris “just made sense,” noting that many European institutions were still largely unaware of Ellis. Plus, Paris is known for its photography market and Ellis himself drew compositional inspiration from French artists such as Pierre Bonnard and Édourard Manet, “which I think you can really see in some of these domestic works,” Madey said, pointing to Mother in a Window (1983).

Darrel Ellis, Mother in a Window (1983). Photo: Margaret Carrigan.

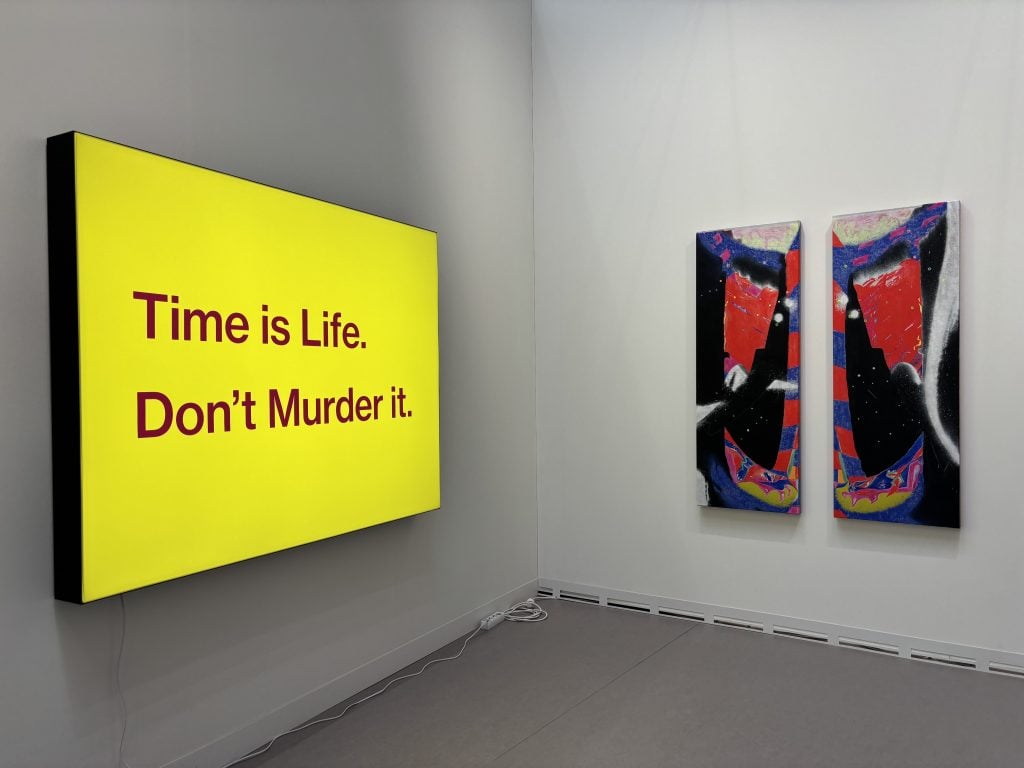

Meanwhile, the Viennese gallery Felix Gaudlitz and LC Queisser of Tbilisi, Georgia have mounted works by five artists at their shared booth, ranging from a text panel by Tony Cokes, brought by Felix Gaudlitz, to a large, bright canvas by Stefanie Heinz, who is on LC Queisser’s roster. At the center of the booth is a work by Simon Lässig, of whom the galleries recently took on joint representation. (Prices for the works at the stand range from $6,000 to $150,000.) The galleries had previously joined forces to present at Miart.

London’s Emalin decided to share a booth with L.A.’s Commonwealth and Council after the former began representing the latter’s artist, Nikita Gale, in Europe last year. Works by Gale, priced between $30,000 and $50,000, are being shown alongside newly created paintings by Leslie Martinez from Commonwealth and Council’s program and sculptural assemblages by Daiga Grantina from Emalin’s.

Risk and Reward

Galleries who opt to split a booth must still submit individual applications outlining the proposed collaboration. In some cases, these are initiated as curatorial ventures, but more often they are a cost-saving measure, which may also explain the increased popularity of partnership, given the challenging market conditions of the last year.

Like booths occupied by one gallery, the cost of a shared booth is based on its size and location—but at least there are two firms to split the bill. All dealers sharing a booth this year—10 in total—are located upstairs, where visibility is lower and square footage is cheaper.

A work by Tony Cokes (left) and Edith Deyerling at Felix Gaudlitz and LC Queisser’s Art Basel Paris booth. Photo: Margaret Carrigan.

“The economics of doing a fair are difficult for most galleries,” said Rosen, adding that sharing a stand at an Art Basel edition is “a good stepping stone for smaller galleries” since it allows them to divide the expenses while still gaining the exposure a major fair offers.

The booth costs are conventionally split equally between the exhibitors by the fair organizers. But once in the fair, the galleries are independent proprietors and must decide for themselves how to divvy up sales. Some may opt to keep profits separate, but most dealers exhibiting this year said they are equally sharing the risks as well as the rewards.

“Because of our close working relationship, we decided to split both the costs and the profits of the presentation equally, regardless of who is making the sale,” said Tosia Leniarska of Emalin. Ritter said that true collaboration requires sharing in both the success and the failures. “Although we aren’t presenting co-represented artists, we are splitting everything 50-50, she added.

Changing the Model

Could the shared booth strategy make art fairs into more democratic events? That’s certainly the gist behind Art Collaboration Kyoto (ACK), the fourth edition of which launches in November. The fair requires Japanese galleries to partner with an international gallery; Misako and Rosen will participate with Reykjavik’s i8 gallery this year.

Nikita Gale’s installation is shown alongside paintings by Leslie Martinez at Emalin and Commonwealth and Council’s booth at Art Basel Paris. Photo: Margaret Carrigan.

A spokesperson for Art Basel said the fair encourages applications for joint booths and added that “it’s been exciting to see this opportunity embraced by spaces of all sizes, particularly by our small- and mid-sized galleries.” An additional 10 galleries will also present joint presentations at the Miami Beach edition of the fair in December, including Emalin with Soft Opening, another London gallery; Afriart Gallery of Kampala, Uganda and Lagos’s Rele Gallery, and Madrid’s Espacio Valverde and Fabian Lang of Zurich.

Not only does the booth-buddy strategy allow galleries to gain valuable visibility at a lower cost, it also benefits an established and competitive fair like Art Basel, which receives thousands of applications each year for its fairs despite a limited number of exhibitor slots. By bringing in more quality emerging and mid-tier galleries without increasing overheads with a larger venue—and, crucially, without sacrificing the square footage the blue-chip galleries get—the fair is essentially creating a self-sustaining pipeline of exhibitors (and their clients).

Still, once a gallery is accepted to Art Basel, it is often more likely to be accepted again. This could lead to an uptick in “prioritized” applications, making it even harder for other outfits to get in.

Rosen, however, remains optimistic. “The landscape is changing,” he said, adding that more and more galleries are working together to create the marketplace that they not only want, but need, whether that’s at a fair—or somewhere else.