A British auction house has withdrawn from sale human and ancestral remains, including shrunken heads and skulls, from communities across the globe after criticism from native groups and museums.

Among items initially listed were shrunken heads from the Jivaro people of South America, skulls from the Ekoi people of west Africa and a 19th-century horned human skull from the Naga people of India and Myanmar, the BBC reported.

The Swan auction house in Tetsworth, Oxfordshire removed the items after condemnation from the Forum for Naga Reconciliation (FNR), who called for the items to be repatriated.

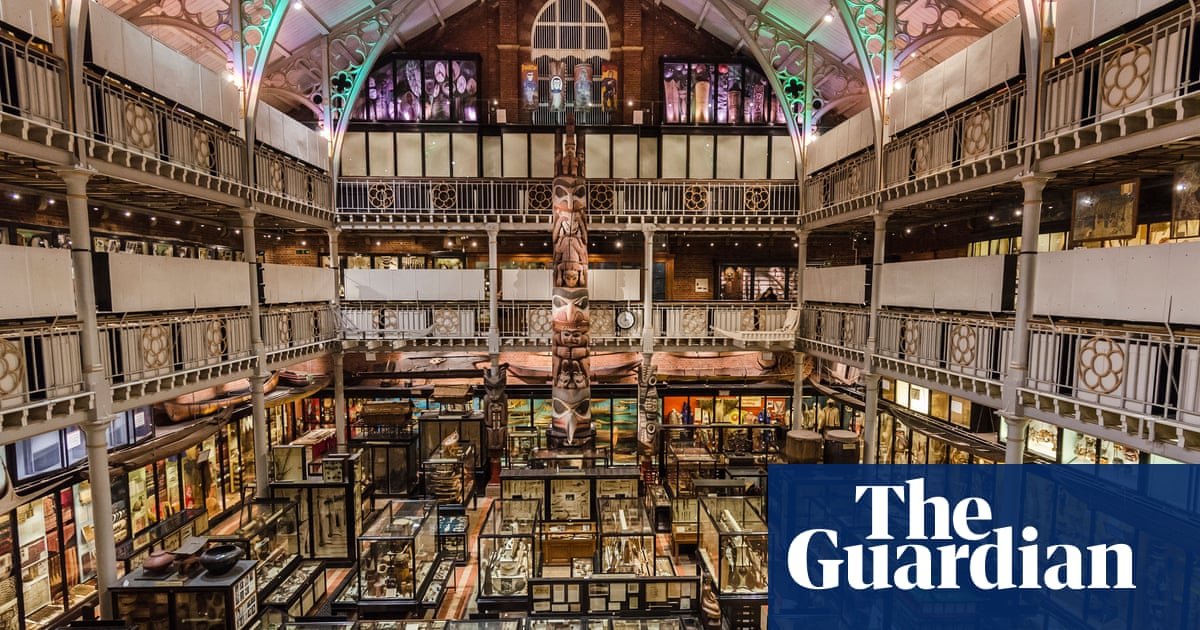

The sale was also criticised by the director of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, which holds such items in its collection and is in dialogue with the communities over the future of such remains.

Neiphiu Rio, the chief minister of the Indian state of Nagaland, condemned the auctioning of human remains as an act of dehumanisation and continued colonial violence, and said it was a highly emotional and sacred issue, Indian media reported. The FNR had directly contacted the auction house.

Laura Van Broekhoven, the director of the Pitt Rivers Museum, told the BBC she was “outraged” at the proposed auction and praised the decision to remove the items. The sale was “ethically really problematic” for many communities worldwide, she said.

“The fact these objects were taken is really painful, and the fact that they were being put on sale is really disrespectful and inconsiderate. We’re conscious that the remains would have been collected in the 19th and 20th centuries, but for them to be on sale in 2024 was quite shocking,” she added.

Tom Keane, auctioneer, valuer and owner of The Swan auction house, confirmed the items had been withdrawn after receiving complaints on Tuesday. “We looked into it, we respected the views expressed and we withdrew the items,” he said.

Human remains including shrunken heads were removed from display at the Pitt Rivers Museum in 2020 as part of a “decolonisation process”. The museum, founded in 1884 and focusing on anthropology, ethnology and archaeology, is in dialogue with many Indigenous groups about the future of artefacts held in its collection.

“We are currently reaching out to communities that we have these human remains, and they can tell us how they would like us to care for them or if they would like them to be repatriated,” Van Broekhoven told the BBC.

“All of that is possible when they’re held in public collections like ours. We can be held accountable, whereas once they go up for auction, they’re out of public use and there’s no way for a community to be in contact.”

She added that she “commended” the auction house’s decision to remove the remains from sale – but questioned what would now happen to them.

In May a Dorset auction house withdrew 18 ancient Egyptian human skulls from sale after the Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy said selling them would perpetuate the atrocities of colonialism, and called for the sale of human remains to be outlawed.

The UK has strict regulations on the storage, treatment and display of human remains. But anyone can possess, buy and sell human body parts as long as they were not acquired illegally, and they are not used for transplants, only for decoration.